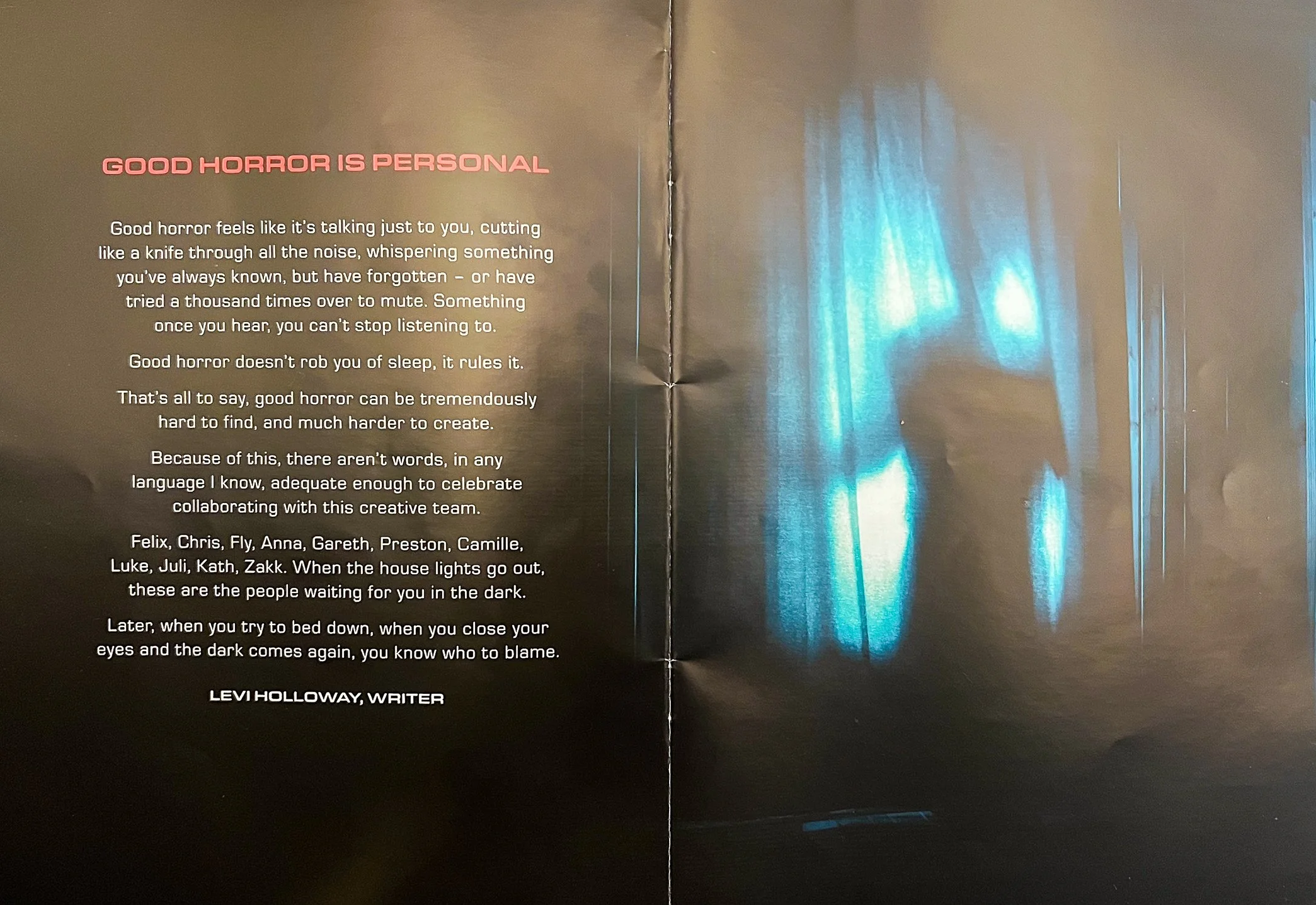

The Ambassadors Theatre is currently hosting “Paranormal Activity”. Written by Levi Holloway and directed by Felix Barrett of Punchdrunk, it follows a couple who begin to experience unsettling events after moving to London. I will not go into plot details to avoid spoilers, but the involvement of Felix Barrett alone was enough to convince us that this was something we should see.

So I got hold of tickets and off we went.

This was our first visit to the Ambassadors Theatre. Built in 1913, it is a Grade II listed building and relatively small by West End standards, seating around 400 to 440 people across two levels, with stalls at ground level and a single dress circle above. The modest size and intimate sightlines mean you are much closer to the actors and the action than in many larger theatres. We were seated downstairs, fairly close to the stage, which worked particularly well for this production.

The exterior is restrained and classical, with a stuccoed façade on West Street, pilasters, a deep cornice and a balustraded parapet. The building occupies a compact, almost triangular site.

Teatr Ambassadors wystawia obecnie „Paranormal Activity”. Autorem tekstu jest Levi Holloway, a reżyserii podjął się Felix Barrett z Punchdrunk. Historia opowiada o parze, która po przeprowadzce do Londynu zaczyna doświadczać niepokojących zdarzeń. Nie będę tu wchodzić w szczegóły, żeby niczego nie zdradzić, ale gdy tylko usłyszałam nazwisko Barretta, wiedziałam, że nie możemy tego przegapić.

Zdobyliśmy zatem bilety i ruszyliśmy do teatru.

Była to nasza pierwsza wizyta w tym teatrze. Budynek powstał w 1913 roku i jest obiektem klasy II na liście zabytków. To raczej kameralna scena jak na West End, mieszcząca około 400–440 widzów, z parterem i jednym balkonem. Dzięki niewielkim rozmiarom i dobrym proporcjom widowni ma się poczucie bliskości z aktorami i samą akcją. My siedzieliśmy na dole, dość blisko sceny, co w przypadku tego spektaklu było dużym plusem.

Z zewnątrz teatr prezentuje się dość powściągliwie, w klasycznym stylu, ze stiukową fasadą przy West Street, pilastrami i wyraźnym gzymsem. Obszar teatru jest mały i nieregularny, niemal trójkątny.

Inside, the theatre is decorated in an elegant Louis XVI style, with a colour palette traditionally associated with Parma violet, ivory and gold. It feels quite refined. The foyer and public areas feature decorative plasterwork and pilasters, with a pleasing circular space that leads into the auditorium.

We arrived quite early and had a drink. As the bar area is very small, and the auditorium had not yet opened, we waited in the corridor, sitting on the floor and using the time to unwind a little before being let in to find our seats.

Wnętrze zaskakuje eleganckim wystrojem w stylu Ludwika XVI, z paletą kolorów, w której dominuje fiolet, kość słoniowa i złoto. Całość jest dość wyrafinowana. Przestrzenie foyer mają dekoracyjne sztukaterie i przyjemny, półkolisty układ prowadzący do widowni.

Przyjechaliśmy dość wcześnie i mieliśmy sporo czasu, żeby napić się czegoś przed spektaklem. Bar jest jednak bardzo mały, a ponieważ widownia nie była jeszcze otwarta, rozsiedliśmy się na podłodze korytarza.

The play itself is highly atmospheric and genuinely unsettling without tipping into tackiness. The tone is creeping and tense, often very quiet, until it suddenly is not. The set represents a London home, shown as a cross-section over two floors, like a doll-house with one wall removed. Sound design, darkness and practical stage effects are used extensively, with some moments that feel closer to stage magic than conventional theatre, and which we are still trying to work out.

Silence is used deliberately and effectively, to the point where you can hear the audience holding its breath or reacting audibly. Modern horror does not often manage to sustain this level of unease, but this production does.

To sum it up, we liked it a great deal.

Sam spektakl jest bardzo sugestywny i naprawdę niepokojący, ale bez tanich efektów. Nastrój budowany jest powoli i konsekwentnie. Scenografia przedstawia londyński dom pokazany w przekroju, na dwóch poziomach, jak domek dla lalek bez jednej ściany. Ogromną rolę odgrywa dźwięk, światło (lub jego brak) i efekty realizowane na żywo. Niektóre z nich przypominają sztuczki iluzjonistyczne i do tej pory nie jesteśmy pewni, jak zostały zrobione. Cisza jest także używana w tym przedstawieniu bardzo świadomie. Widać i słychać reakcje widowni, w tym wstrzymywanie oddechu. Współczesny horror rzadko potrafi wywołać taki poziom napięcia, a tutaj to się ewidentnie udało.

Krótko mowiąć, bardzo nam się ten spektakl podobał.