As we are close to Plaza Regocijo, we decide to pop into the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, which is housed in the historic Municipal Palace, also known as the Palacio del Cabildo. We are mostly drawn in by the colonial architecture, as the palace was built in 1848. The exterior has a strong colonial feel, with a double row of arches and classic stonework, some of it repurposed from a demolished Augustinian convent.

Inside, the central courtyard is peaceful and elegant, with a fountain at its centre and arcaded galleries running along the ground and upper levels.

Skoro już jesteśmy w pobliżu Plaza Regocijo, postanawiamy zajrzeć na chwilę do Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, które mieści się w zabytkowym Pałacu Miejskim, znanym jako Palacio del Cabildo. Przyciąga nas przede wszystkim kolonialna architektura - budynek pochodzi z 1848 roku. Z zewnątrz robi wrażenie dzięki dwóm rzędom arkad i solidnemu kamiennemu wykończeniu (kamienie te częściowo pochodzą z rozebranego klasztoru augustianów).

Wewnątrz znajduje się spokojny dziedziniec z fontanną, otoczony arkadowymi krużgankami na parterze i piętrze.

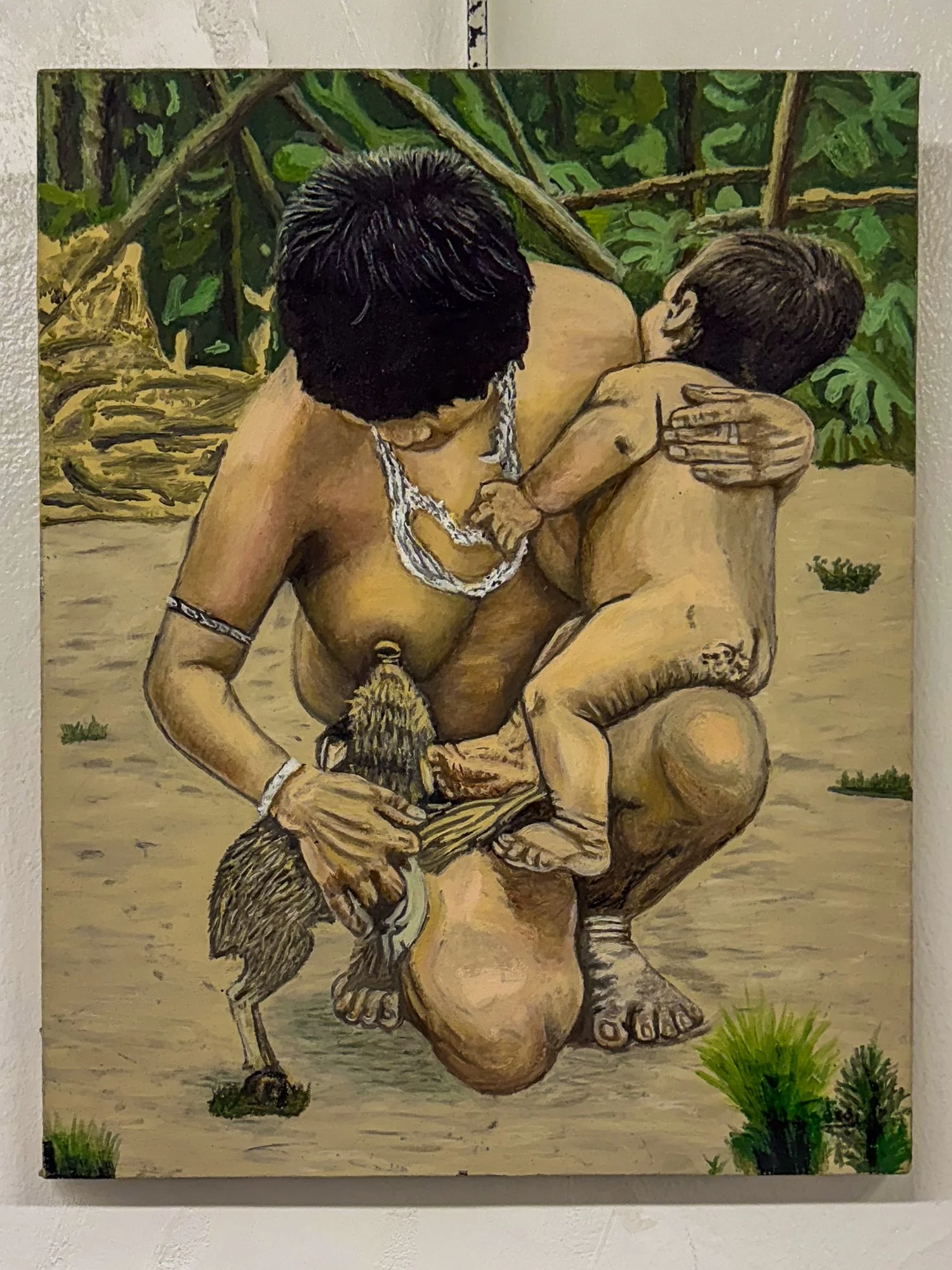

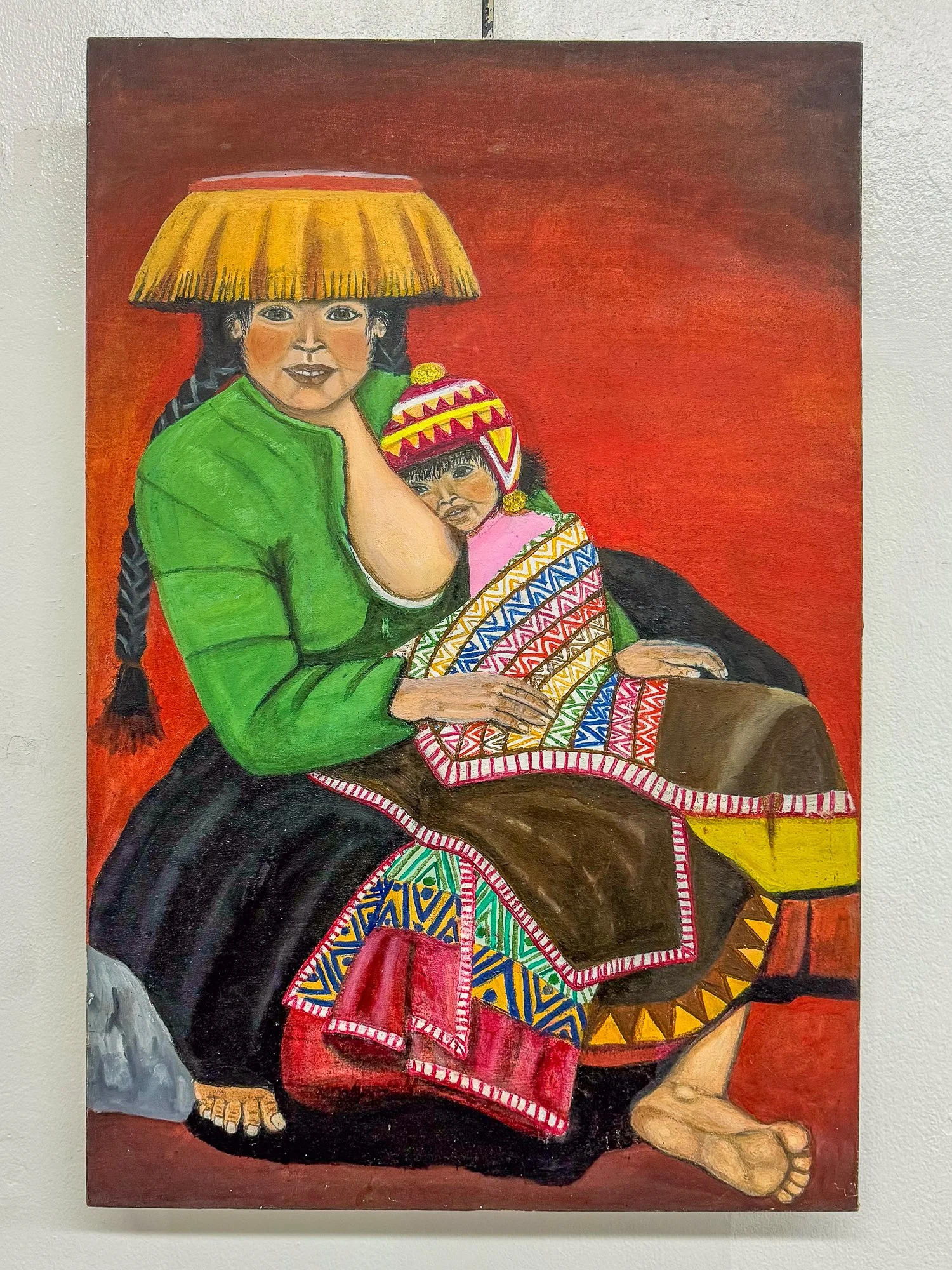

The museum has three main exhibition rooms. Two are on the first floor—one of them tucked into a smaller interior courtyard with striking wooden balustrades painted in vivid blue. The design creates a balcony-like walkway on the upper level, letting you look down and take in the artworks displayed below.

W muzeum są trzy główne sale wystawowe. Dwie z nich znajdują się na parterze — jedna mieści się w mniejszym, wewnętrznym dziedzińcu, który wyróżnia się drewnianymi balustradami pomalowanymi na intensywny niebieski kolor. Układ tej przestrzeni pozwala spacerować po górnym balkonie i oglądać prace prezentowane poniżej.

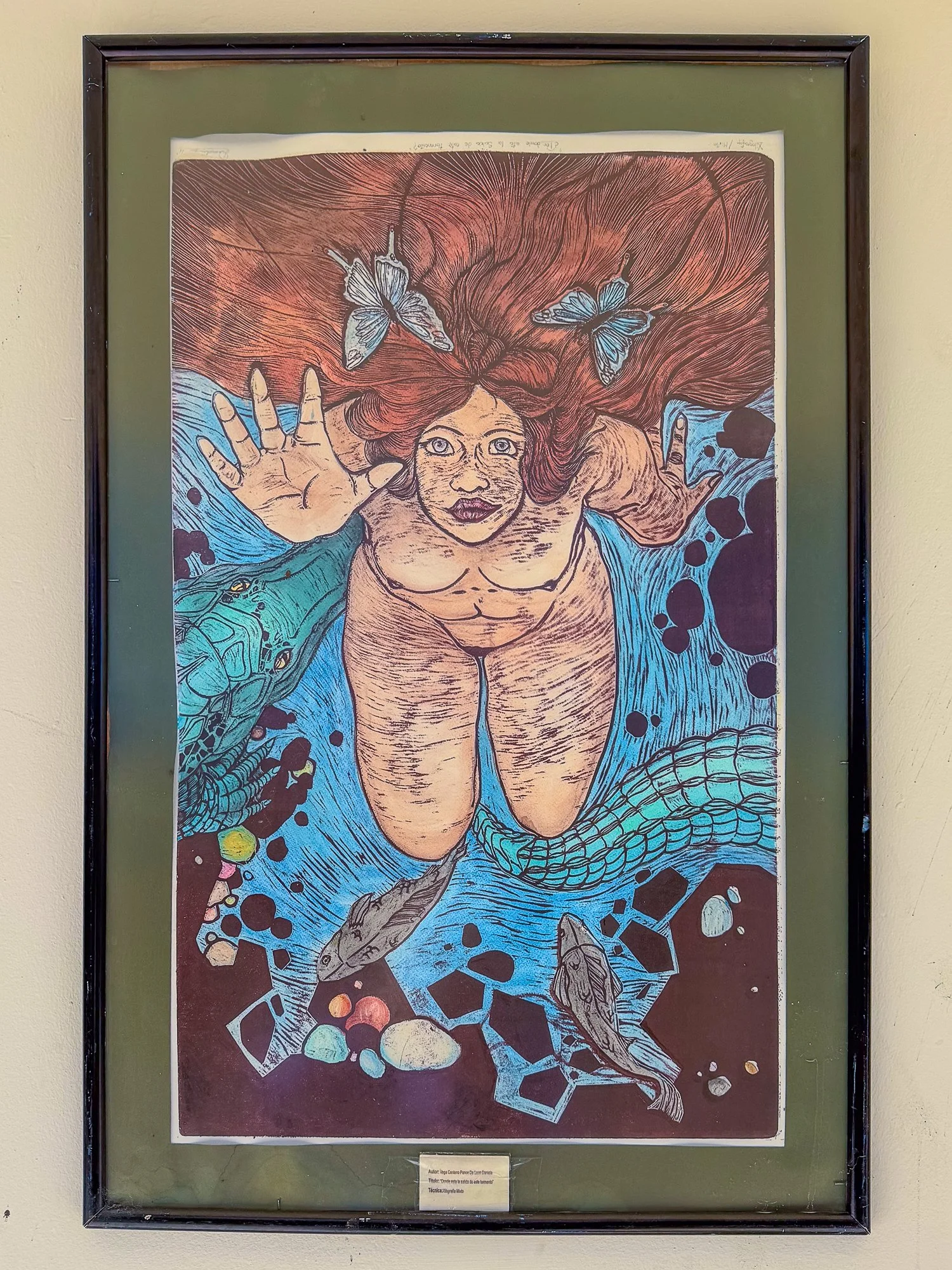

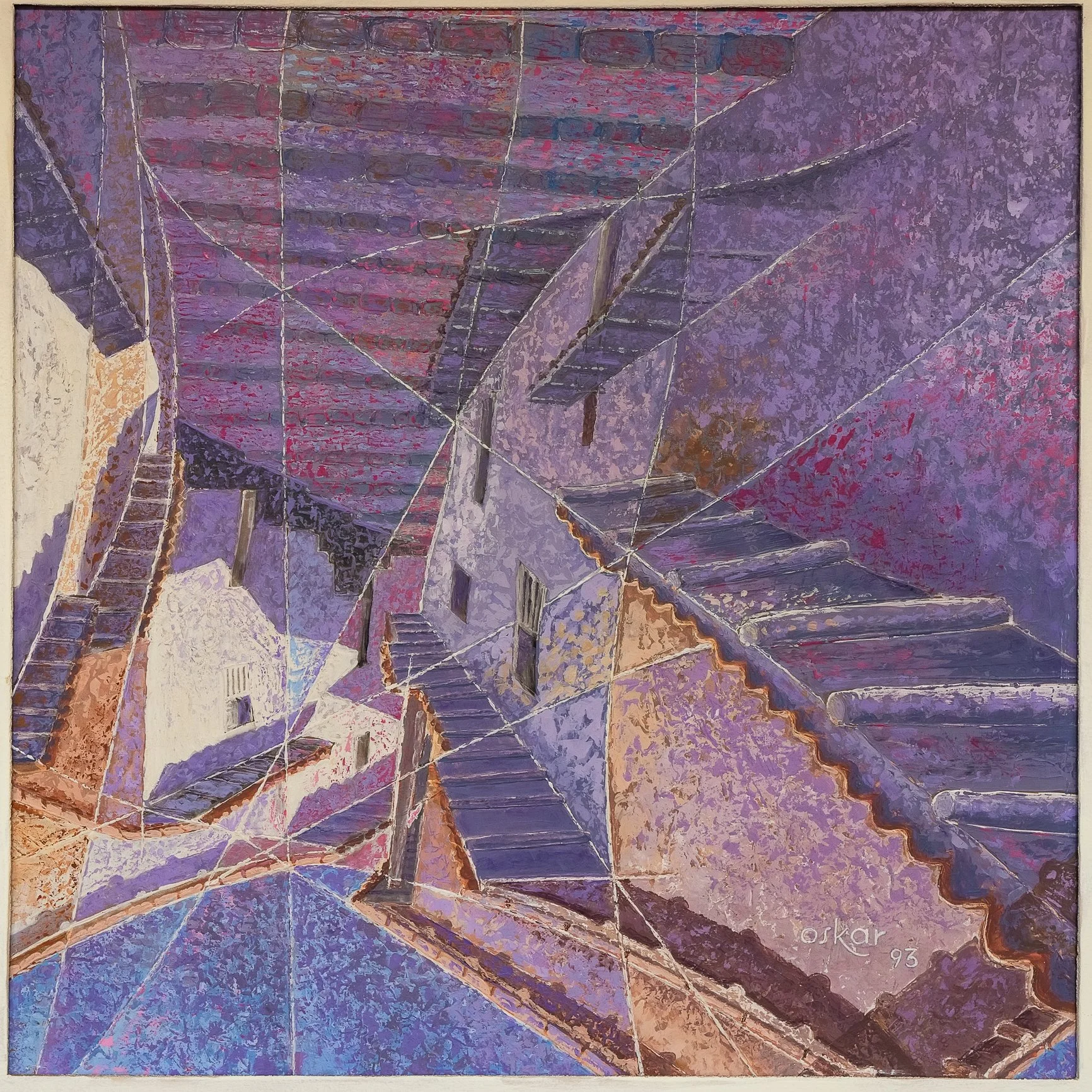

The third exhibition area is on the second floor, located in the upper gallery spaces.

Trzeci obszar ekspozycji znajduje się w galeriach na piętrze.

Cusqueño handicrafts and contemporary art are also on display in glass showcases around the main courtyard.

W głównym dziedzińcu można również zobaczyć ekspozycje współczesnego rękodzieła i sztuki Cusco, umieszczone w przeszklonych gablotach.