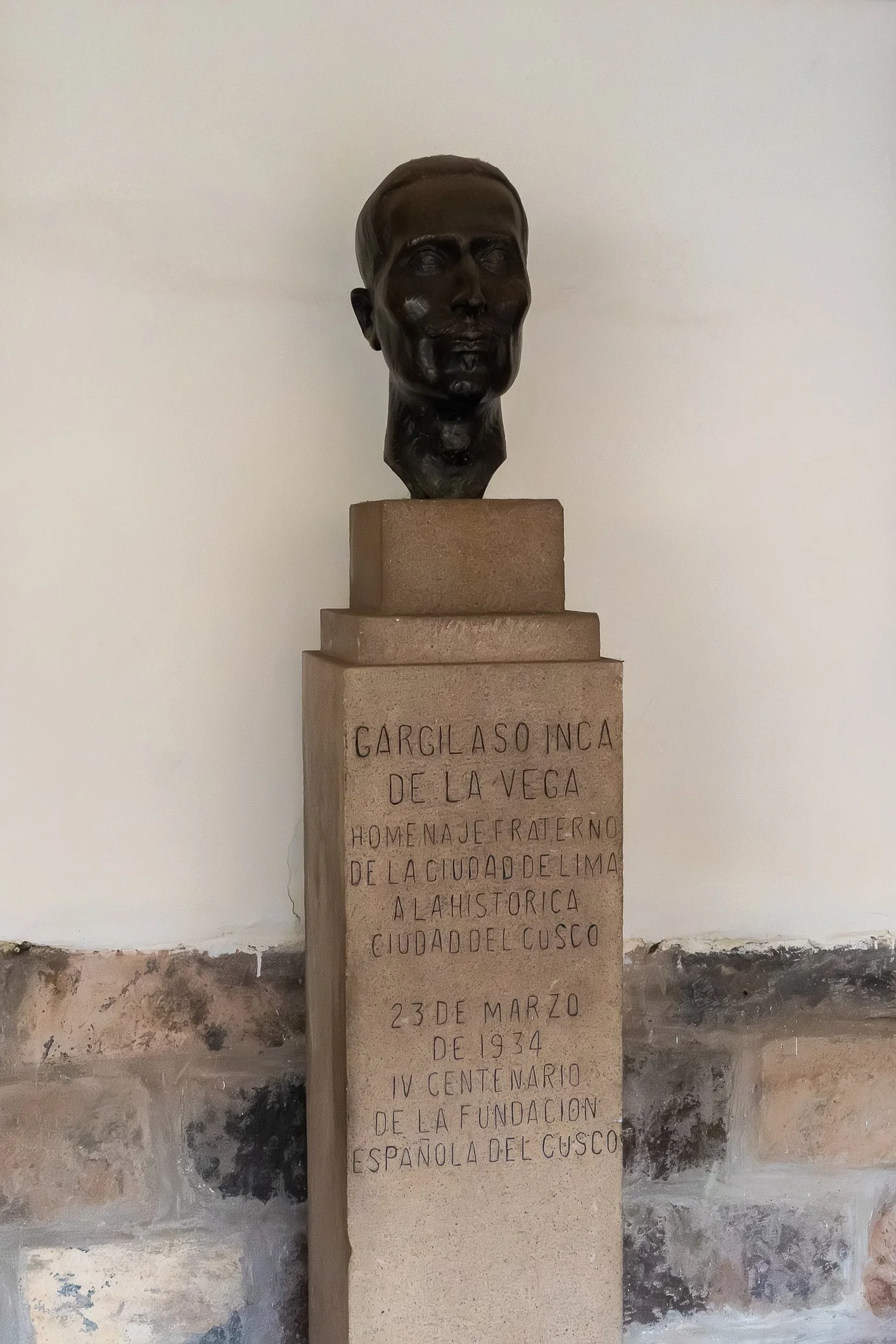

Museo Histórico Regional, also known as Casa Garcilaso, is located near the Plaza de Armas, tucked into a colonial building that used to be the home of the half-Inka, half-Spanish Garcilaso de la Vega — a mestizo writer who became one of the first to write about the Inca world from both Spanish and indigenous perspectives. He wrote several books throughout his lifetime, including a history of Peru that told a story and truth much different from that of the Spanish conquistadors.

From the outside, the building looks like a classic colonial house: cream walls, wooden balconies, and a tiled roof.

Museo Histórico Regional, znane też jako Casa Garcilaso, znajduje się niedaleko Plaza de Armas, ukryte w kolonialnym budynku, który kiedyś był domem Garcilaso de la Vega — pisarza o mieszanym pochodzeniu inkaskim i hiszpańskim. Był jednym z pierwszych, którzy opisywali świat Inków zarówno z perspektywy Hiszpanów, jak i rdzennych mieszkańców. W ciągu życia napisał kilka książek, w tym historię Peru, która przedstawiała zupełnie inne spojrzenie niż hiszpańscy konkwistadorzy.

Z zewnątrz budynek wygląda jak typowy kolonialny dom: kremowe ściany, drewniane balkony i dach pokryty dachówką.

Once we stepped in, we could see the Inca stonework at the base of the walls (not unusual in the Cusco area). The rest is a classical Andean colonial courtyard: rectangular in shape, with arched stone arcades on the ground level and wooden balconies wrapping around the upper floor. The whitewashed walls and terracotta tiles complete the look. That mix of Spanish and Inca architecture kind of sets the tone for the whole museum.

Po wejściu od razu zauważyliśmy inkaskie kamienne mury u podstawy ścian (co jest nie jest w Cusco rzadko spotykane). Poza tym to klasyczny andyjski kolonialny dziedziniec: prostokątny, z kamiennymi arkadami na parterze i drewnianymi balkonami na piętrze. Białe tynki i czerwone dachówki dopełniają całości. To połączenie architektury hiszpańskiej i inkaskiej dobrze oddaje charakter całego muzeum.

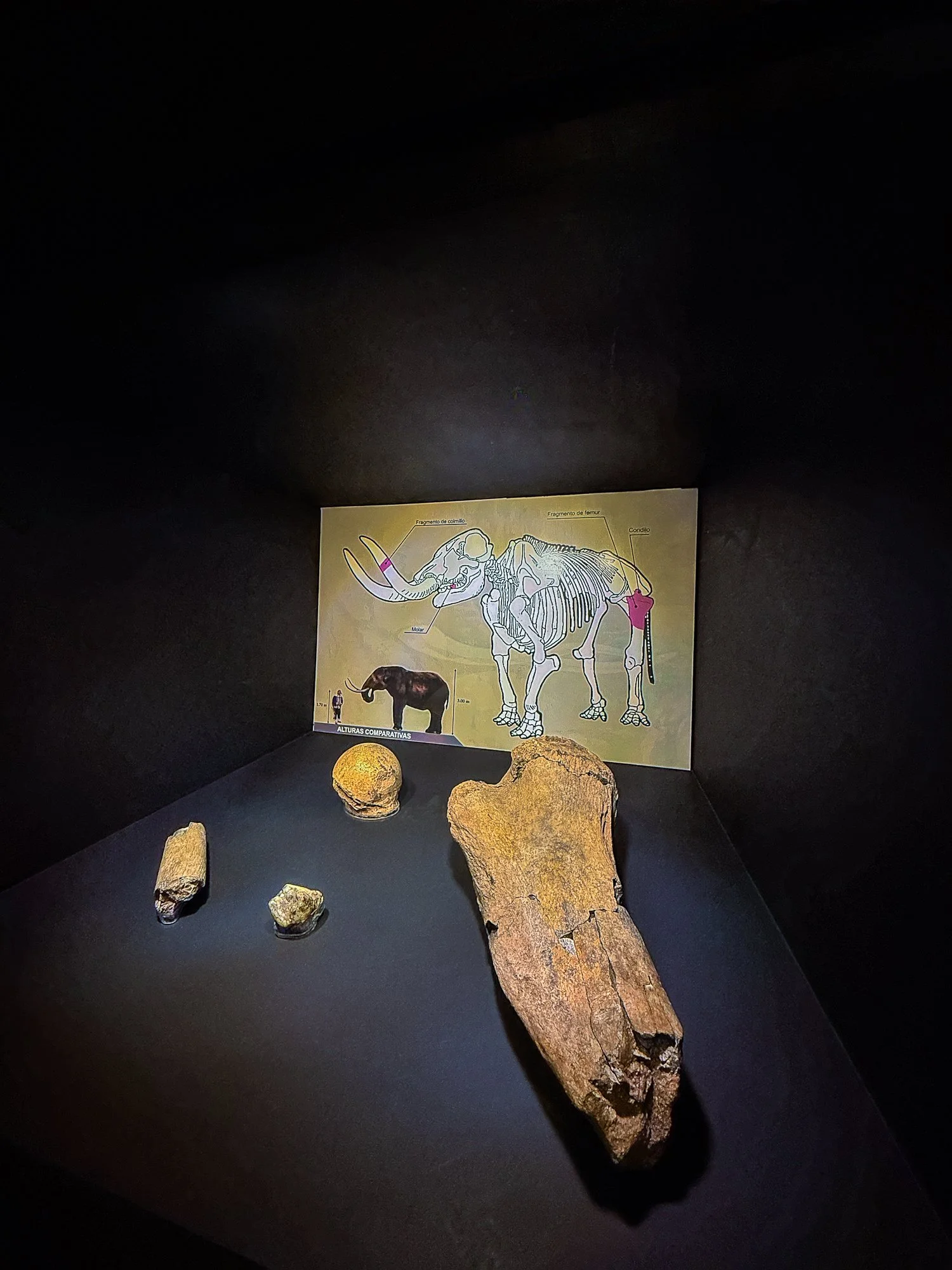

The ground floor of the museum focuses on Cusco’s early history, starting thousands of years before the Incas. There are six rooms on this level, each with a specific theme. The first room has fossils and bones from prehistoric animals — mastodons, giant sloths, and glyptodons that once lived in the area.

Parter poświęcony jest wczesnej historii Cusco, sięgającej tysiące lat przed Inkami. Znajduje się tam sześć sal, każda o innej tematyce. W pierwszej zobaczyliśmy skamieniałości i kości prehistorycznych zwierząt — mastodontów, olbrzymich leniwców i gliptodonów, które kiedyś zamieszkiwały te tereny

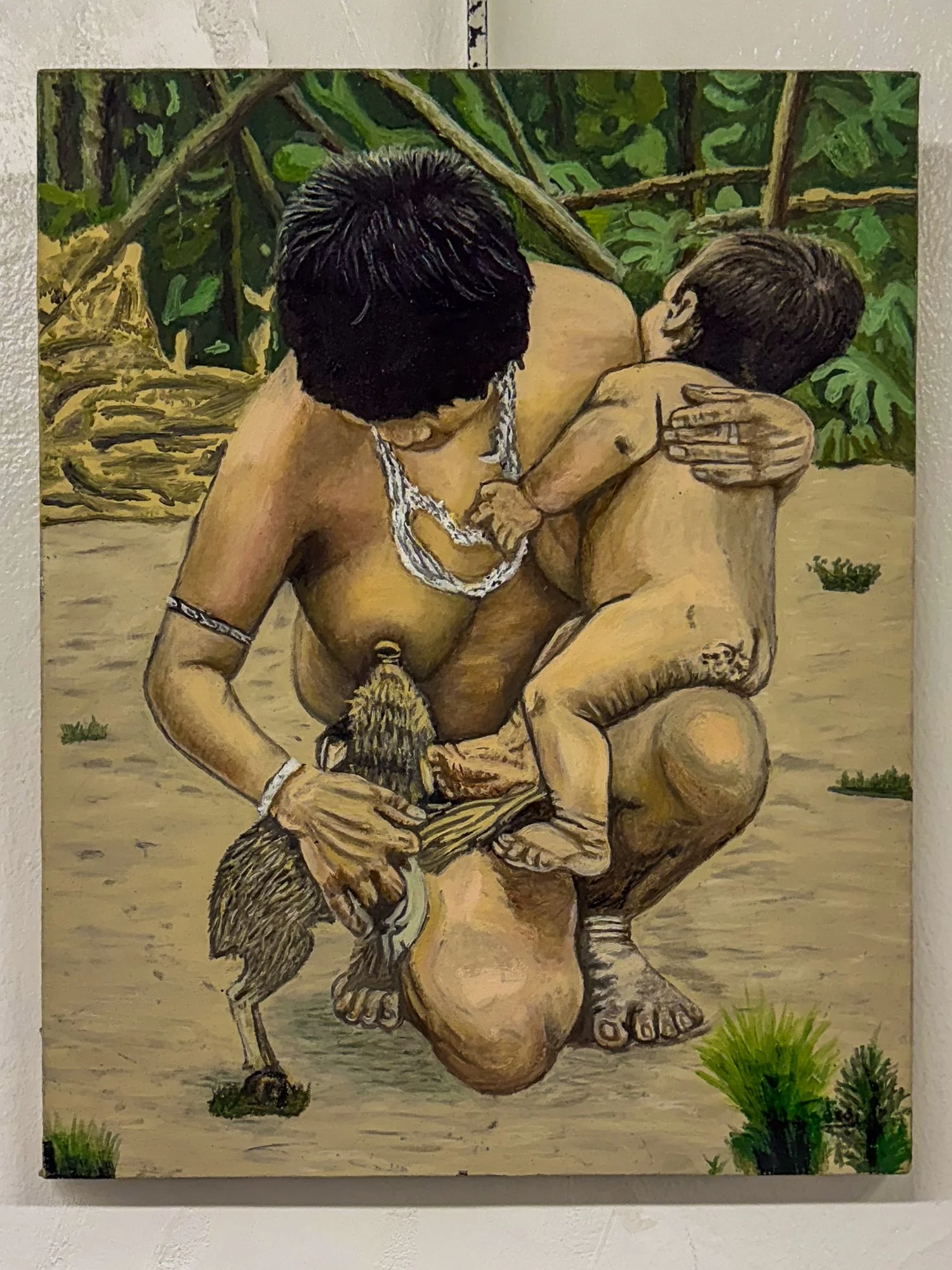

Next is a room about the first people in the Andes. There are tools, stone knives, and fragments of cave art from sites around Cusco.

Kolejna sala opowiada o pierwszych ludziach w Andach. Prezentowane są tu narzędzia, kamienne noże oraz fragmenty sztuki naskalnej znalezione w okolicy Cusco.

Then regional societies that existed before the Incas - the Marcavalle, Chanapata, and Qotakalli cultures - are covered. We saw ceramics, burial urns, and household tools. The display shows how these smaller societies helped lay the foundations for the Inca state.

Potem muzeum pokazuje regionalne kultury sprzed Inków - Marcavalle, Chanapata i Qotakalli. Można tam zobaczyć ceramikę, urny grobowe i przedmioty codziennego użytku. Wystawa tłumaczy, jak te mniejsze społeczeństwa pomogły stworzyć fundamenty państwa inkaskiego.

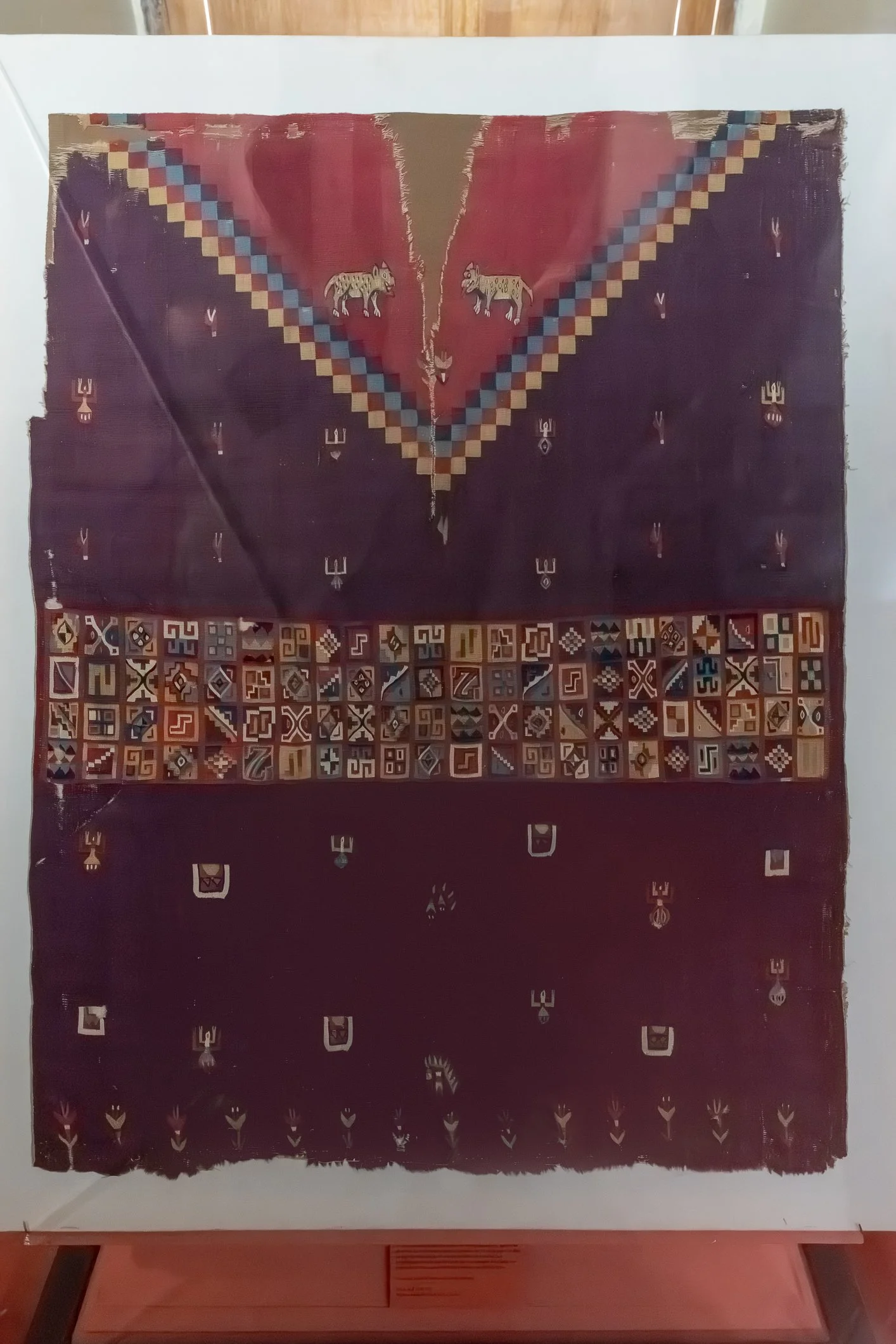

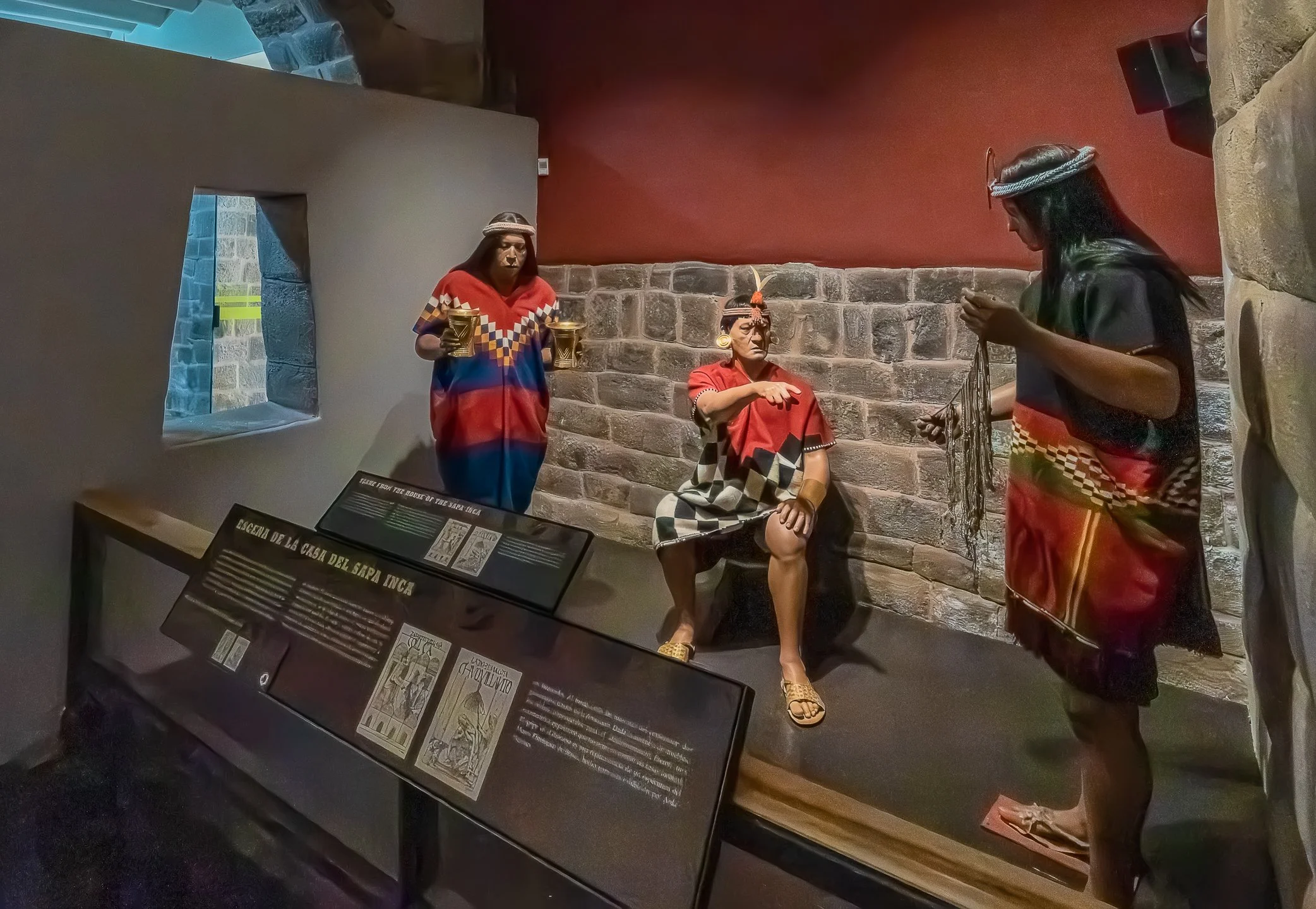

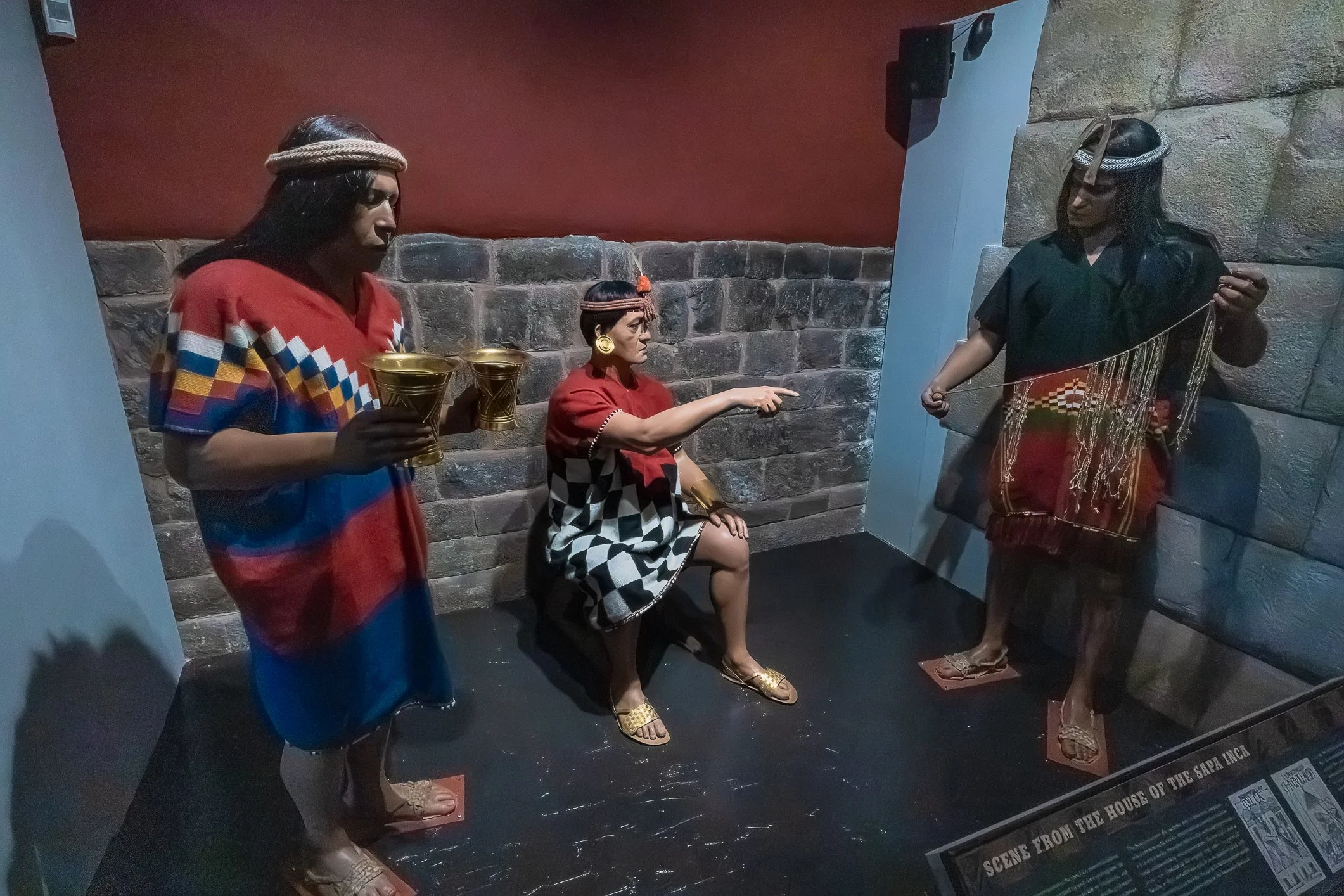

After this, the focus shifts to Inca spirituality. There are carved stones used in rituals - objects that represent mountains (apus), ancestors (mallquis), and natural elements like water or the sun. It gives a good sense of how the Incas viewed the world and their place in it. Subsequently, Inca pottery is depicted - from daily-use items to ceremonial vessels. I saw lots of aríbalos (those large, pointed jars), drinking cups called keros, and bowls painted with geometric patterns and animal figures. Each piece had its own style depending on the region it came from.

Następna sala poświęcona jest duchowości Inków. Prezentowane są wyryte kamienie używane w rytuałach - przedmioty symbolizujące góry (apus), przodków (mallquis) i naturalne elementy, takie jak woda czy słońce. Daje to dobre wyobrażenie o tym, jak Inkowie postrzegali świat i swoje w nim miejsce. Potem można zobaczyć inkaską ceramikę, od naczyń codziennego użytku po te ceremonialne. Widzieliśmy dużo aríbalos (dużych, stożkowatych dzbanów), kubków do picia zwanych keros oraz misek zdobionych geometrycznymi wzorami i zwierzęcymi motywami. Każdy egzemplarz miał swój styl, zależny od regionu, z którego pochodził.

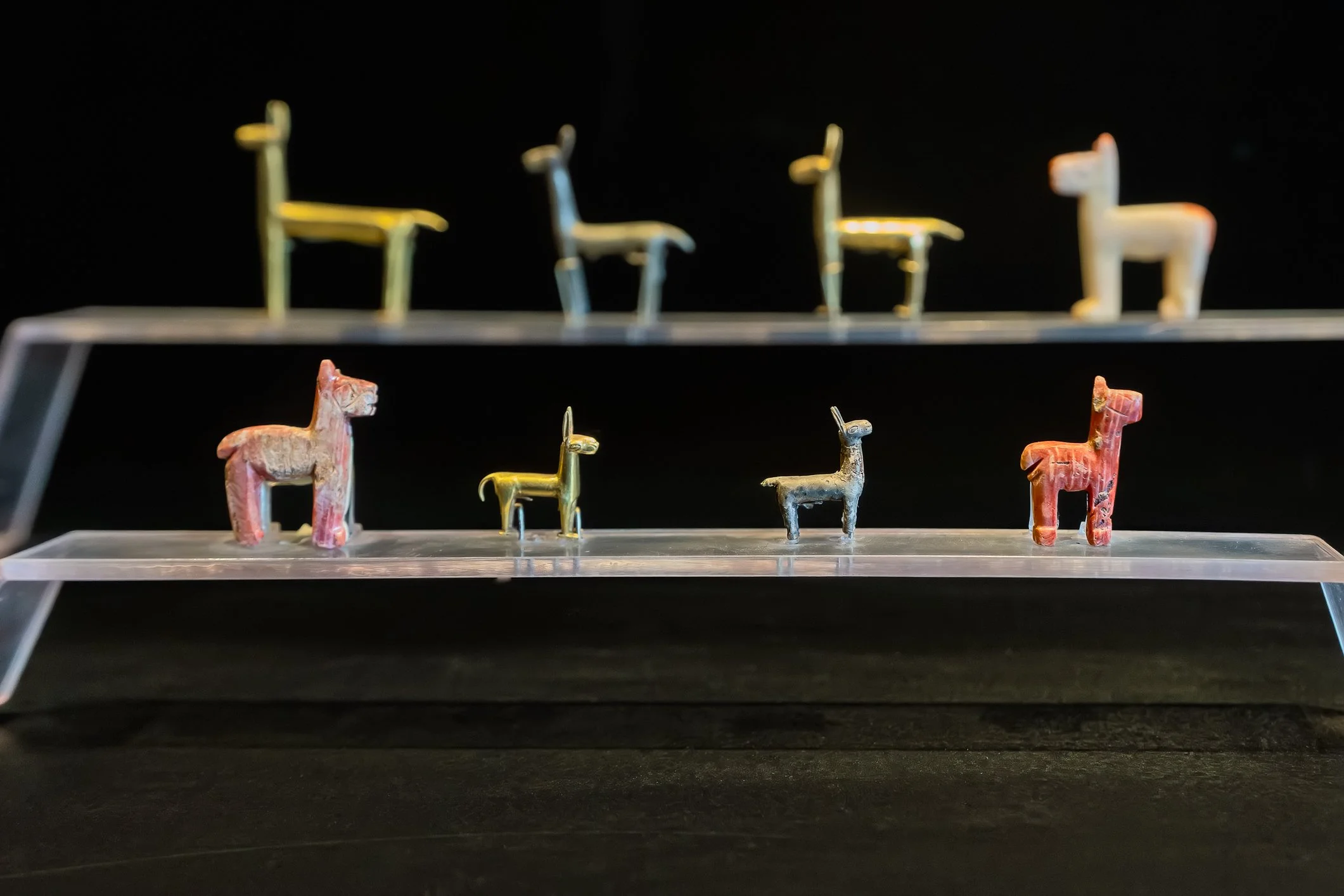

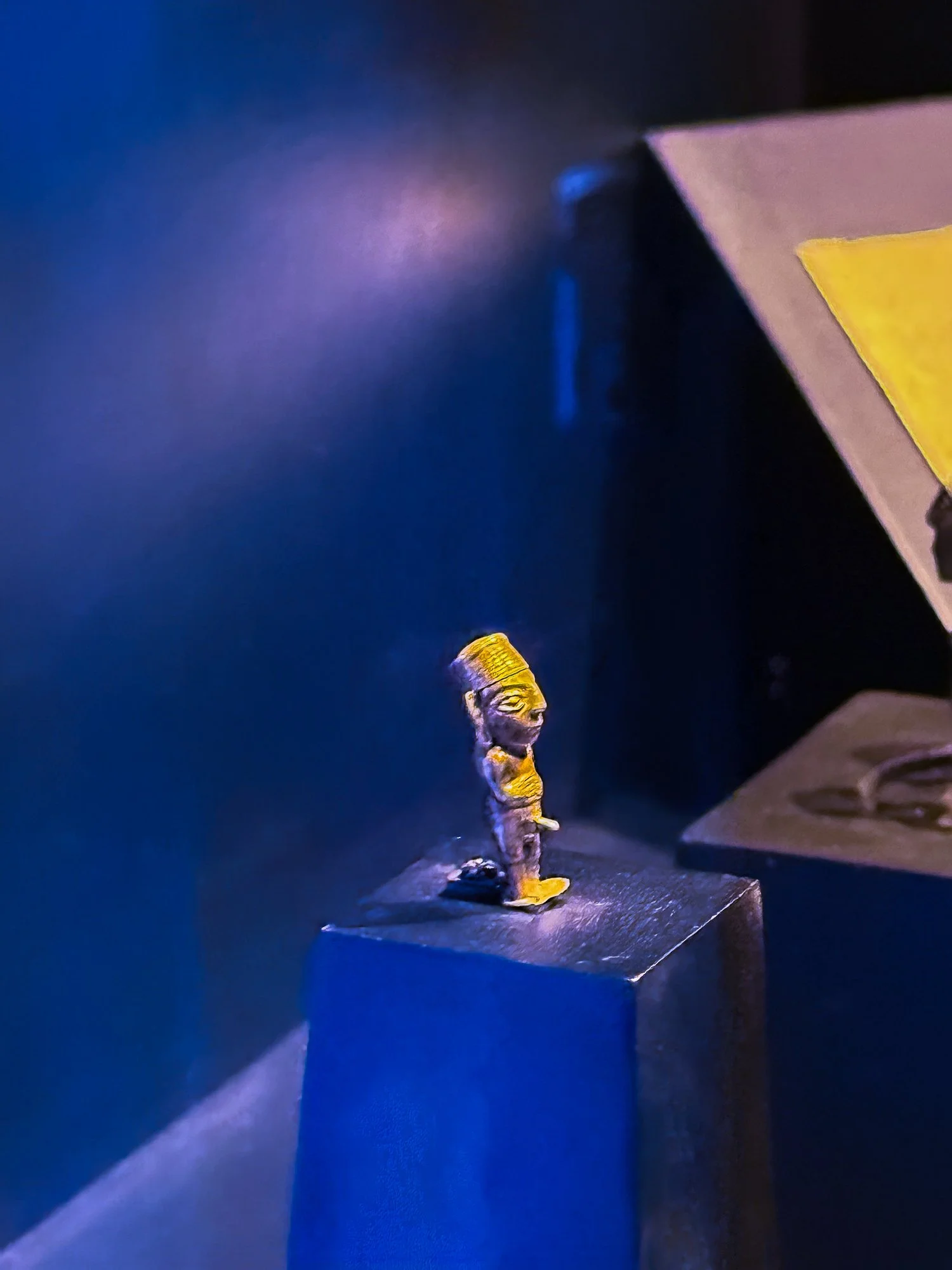

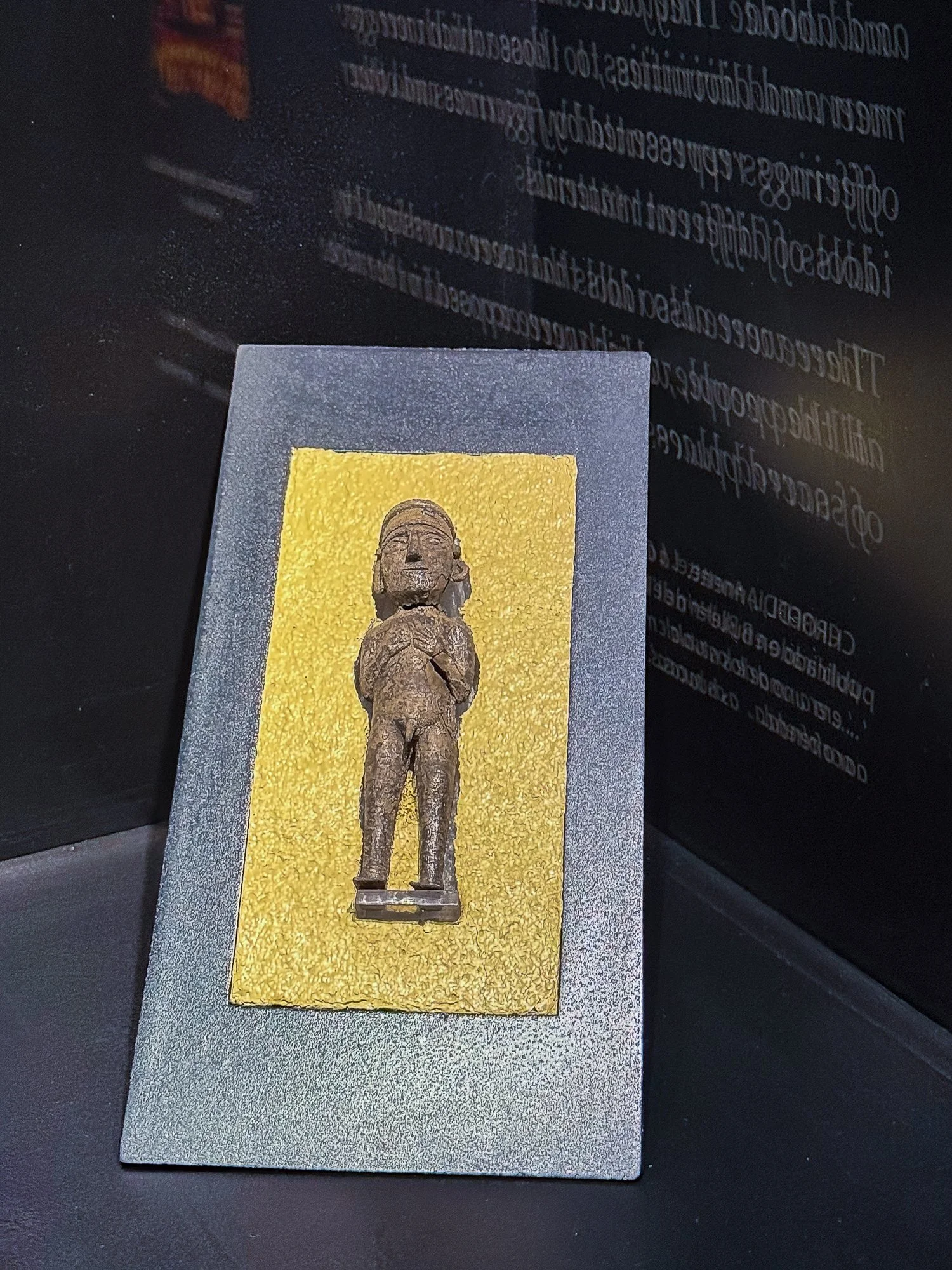

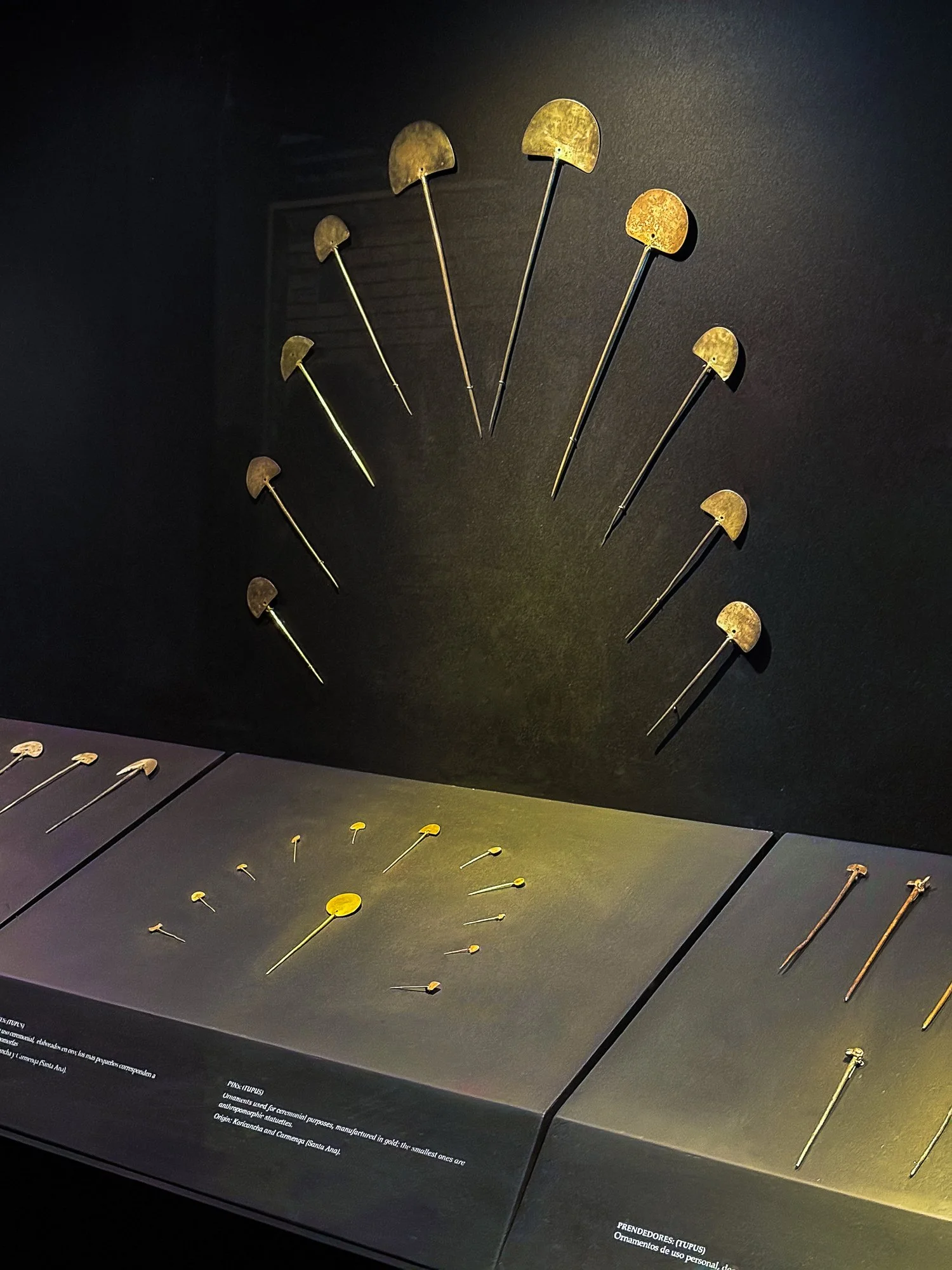

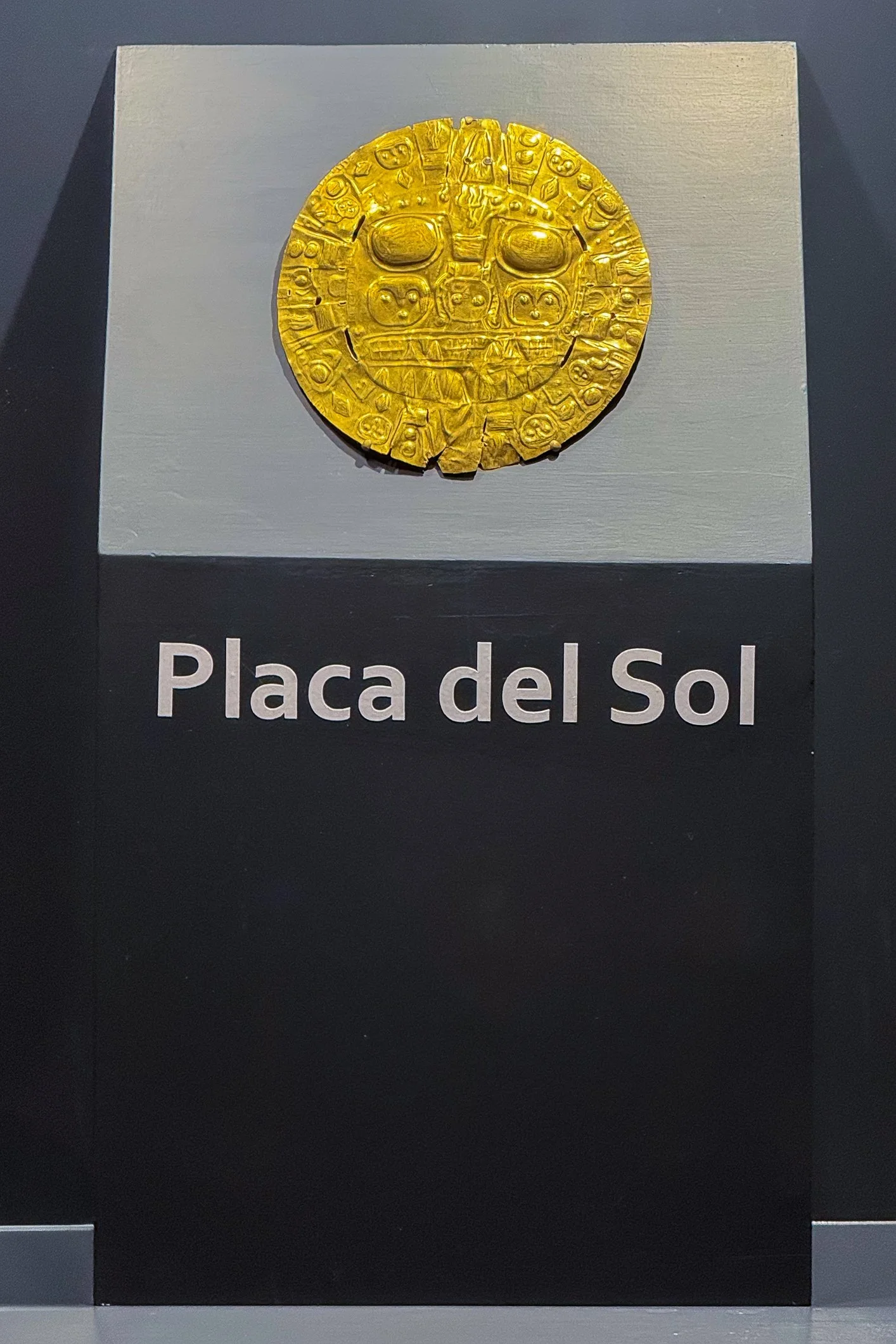

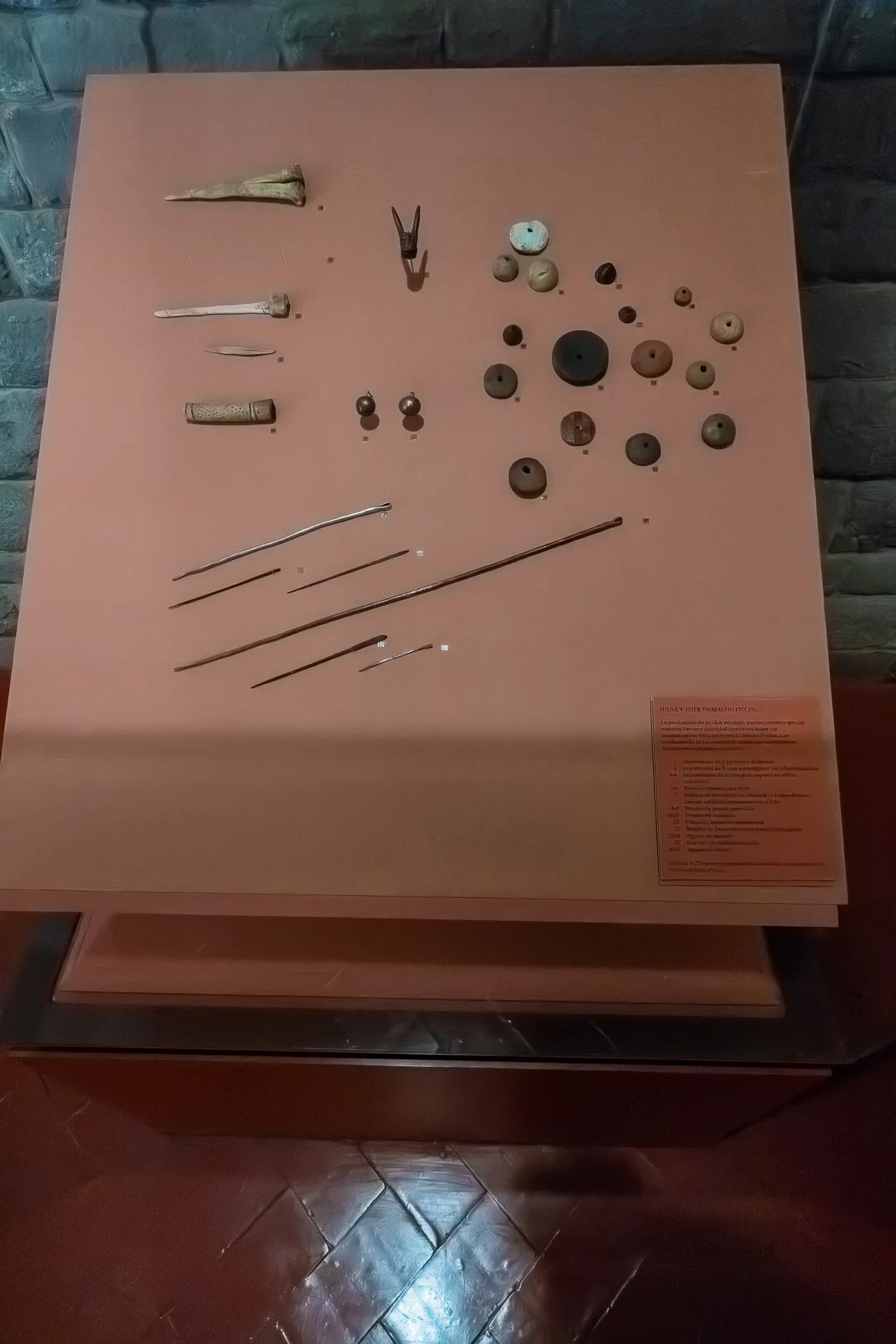

The last room on the ground floor shows how the Incas used gold, silver, and copper not just for jewellery and religious offerings, but also for tools and personal items. There are some gold and silver llama statuettes and mini figurines from Sacsayhuaman. The craftsmanship is quite impressive considering they didn’t use iron or advanced smelting methods.

Ostatnia sala na parterze pokazuje, jak Inkowie wykorzystywali złoto, srebro i miedź - nie tylko do biżuterii i ofiar religijnych, ale też do narzędzi i przedmiotów codziennego użytku. Można tam zobaczyć złote i srebrne figurki lam oraz inne miniaturowe rzeźby z Sacsayhuamán. Wyroby te robią duże wrażenie, zwłaszcza biorąc pod uwagę, że ich twórcy nie umieli jeszcze korzystać z żelaza ani zaawansowanych metod hutniczych.

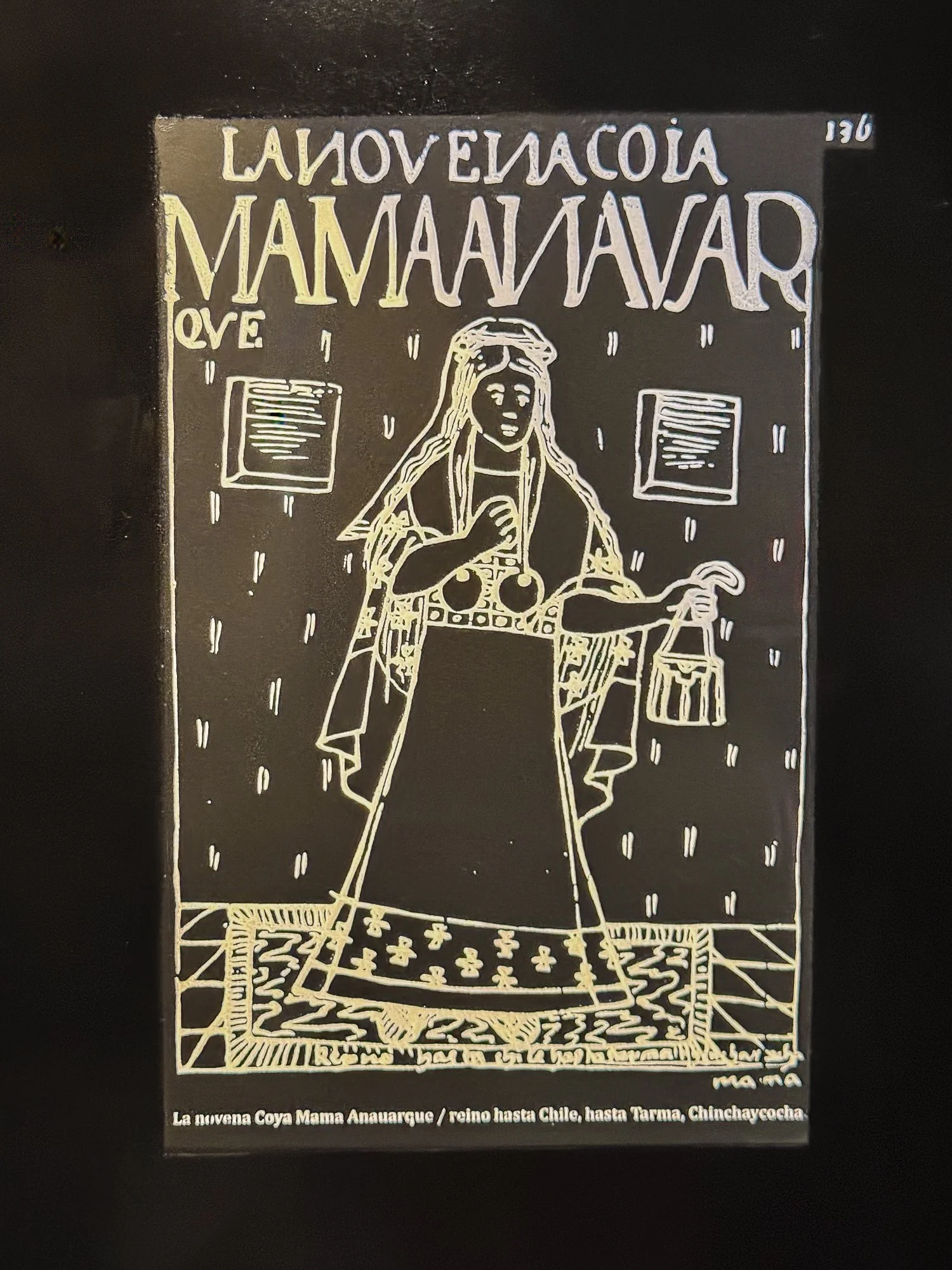

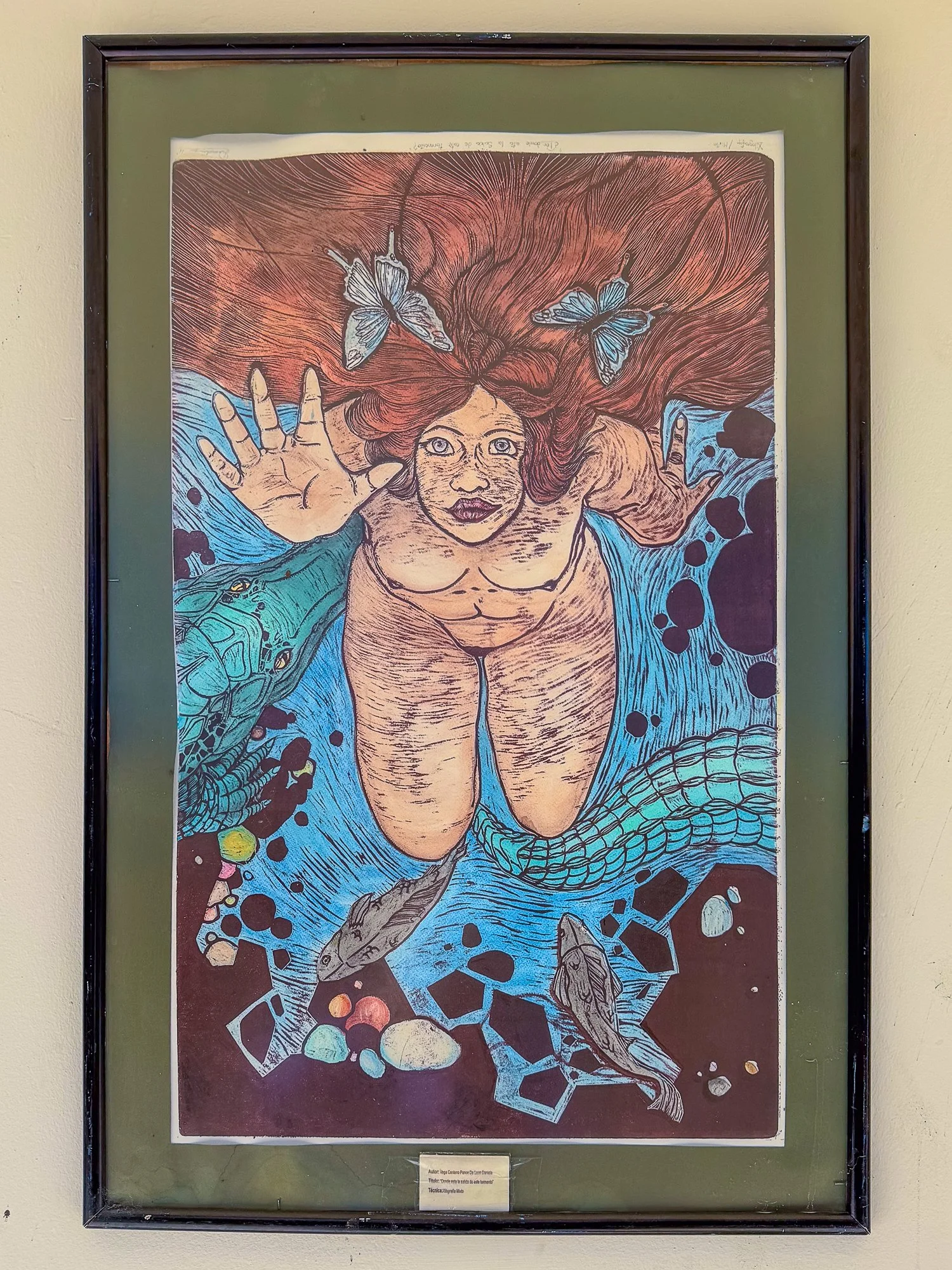

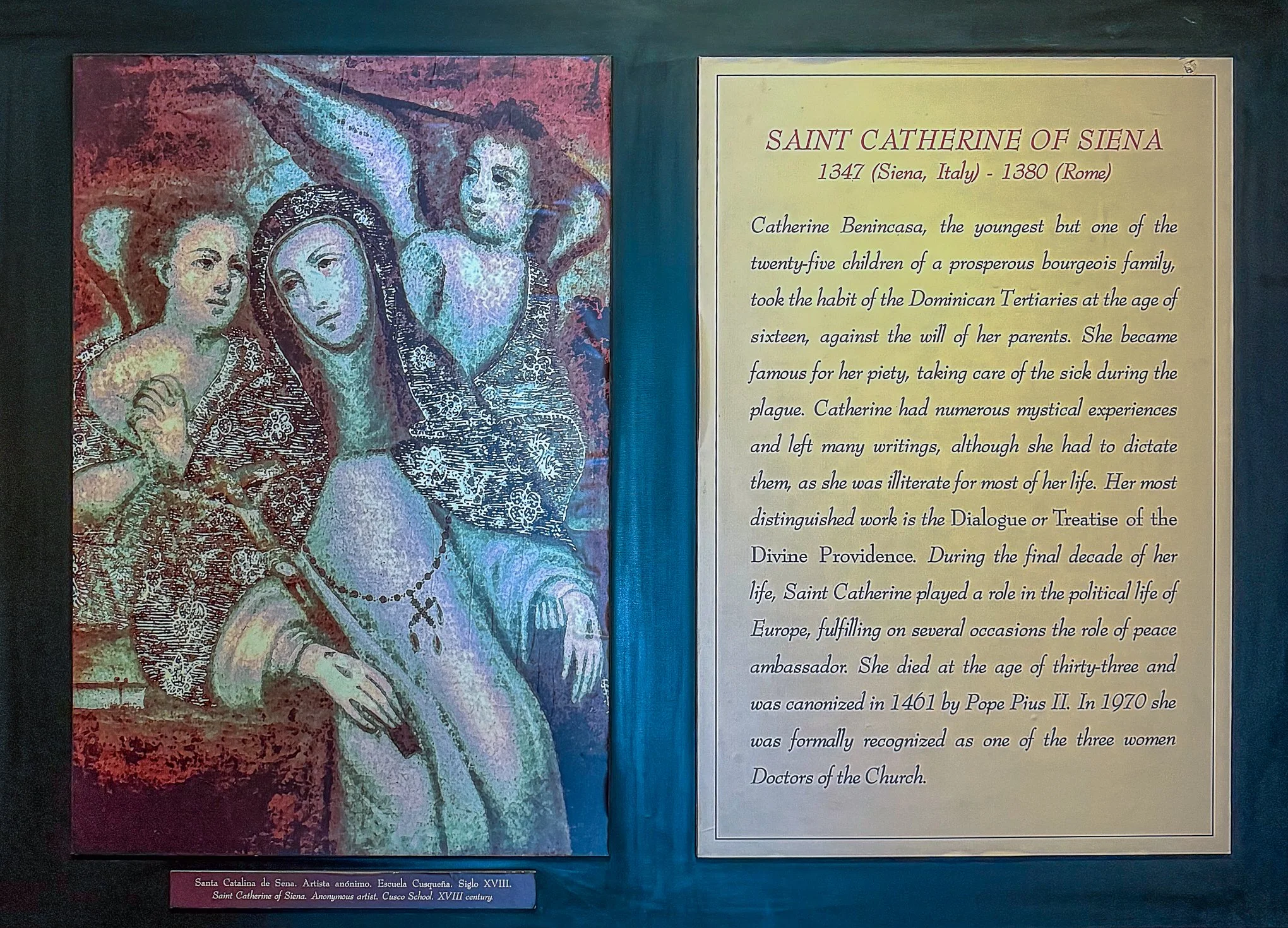

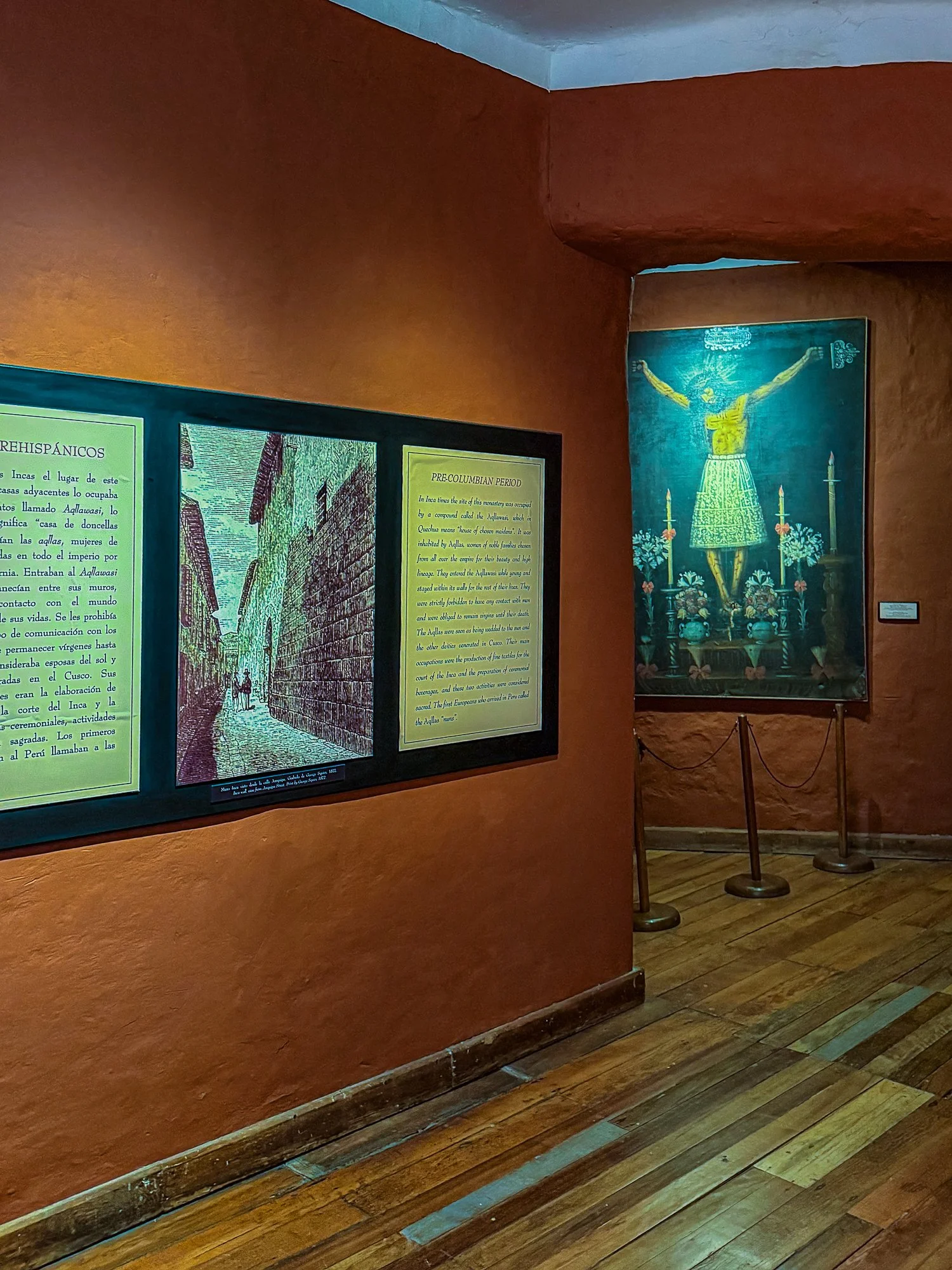

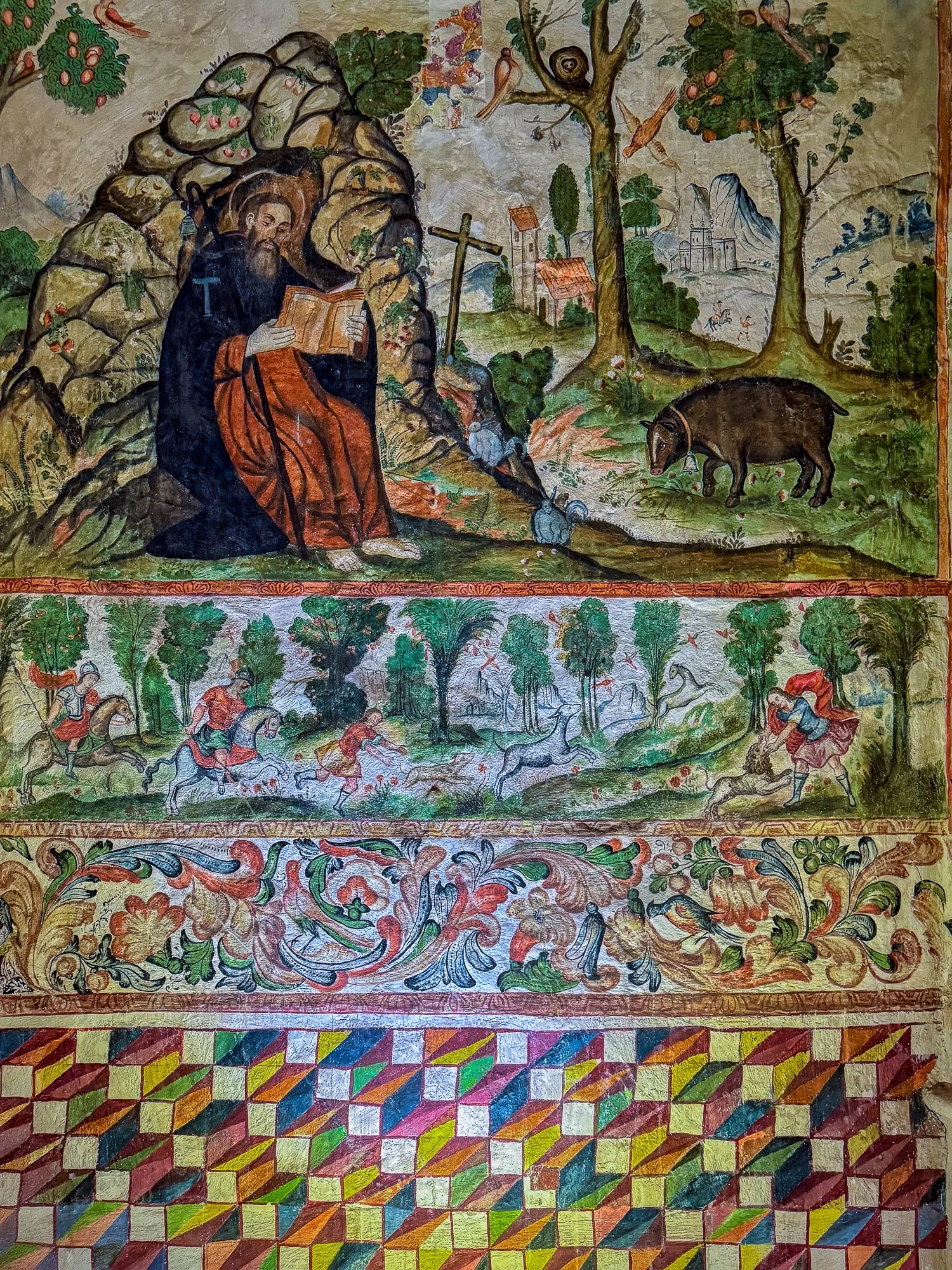

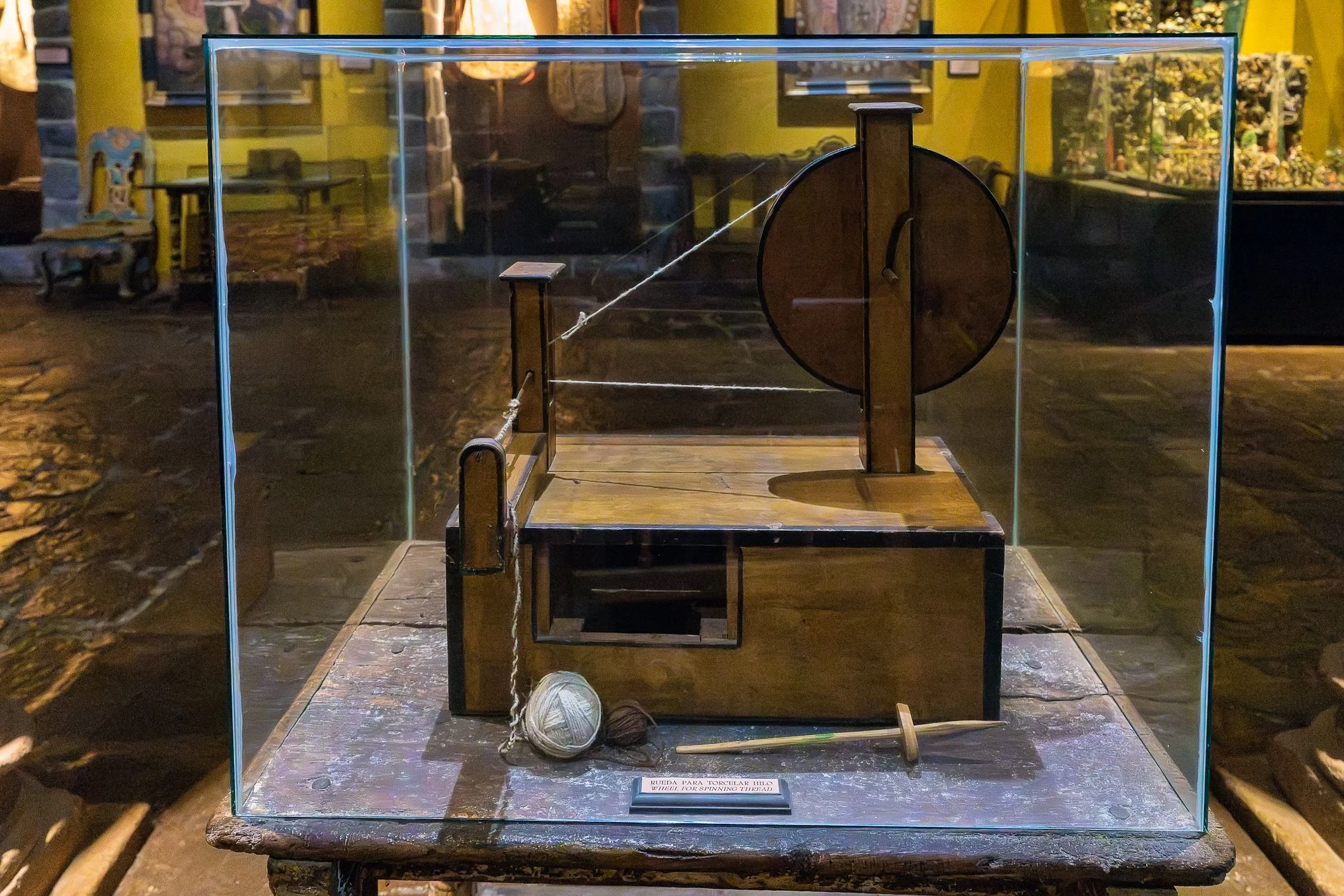

Heading upstairs, the museum shifts focus to the Spanish conquest and colonial period. These rooms are more about religion, art, resistance, and daily life after the Spanish arrived. The first room talks about religious overlap. It explains how Spanish missionaries repurposed native gods to fit Christian figures. For example, the Inca thunder god Illapa was often rebranded as Santiago Matamoros, shown riding a horse and defeating enemies. The artwork here shows how confusing and complex this cultural shift must have been.

Na piętrze muzeum zmienia tematykę na okres hiszpańskiego podboju i kolonizacji. Wystawy bardziej skupiają się na religii, sztuce, oporze i codziennym życiu po przybyciu Hiszpanów. Pierwsza z nich omawia nakładanie się wierzeń - wyjaśnia, jak hiszpańscy misjonarze próbowali przekształcić rodzimych bogów w postacie chrześcijańskie. Na przykład inkański bóg burzy Illapa często był przedstawiany jako Santiago Matamoros, rycerz na koniu pokonujący wrogów.

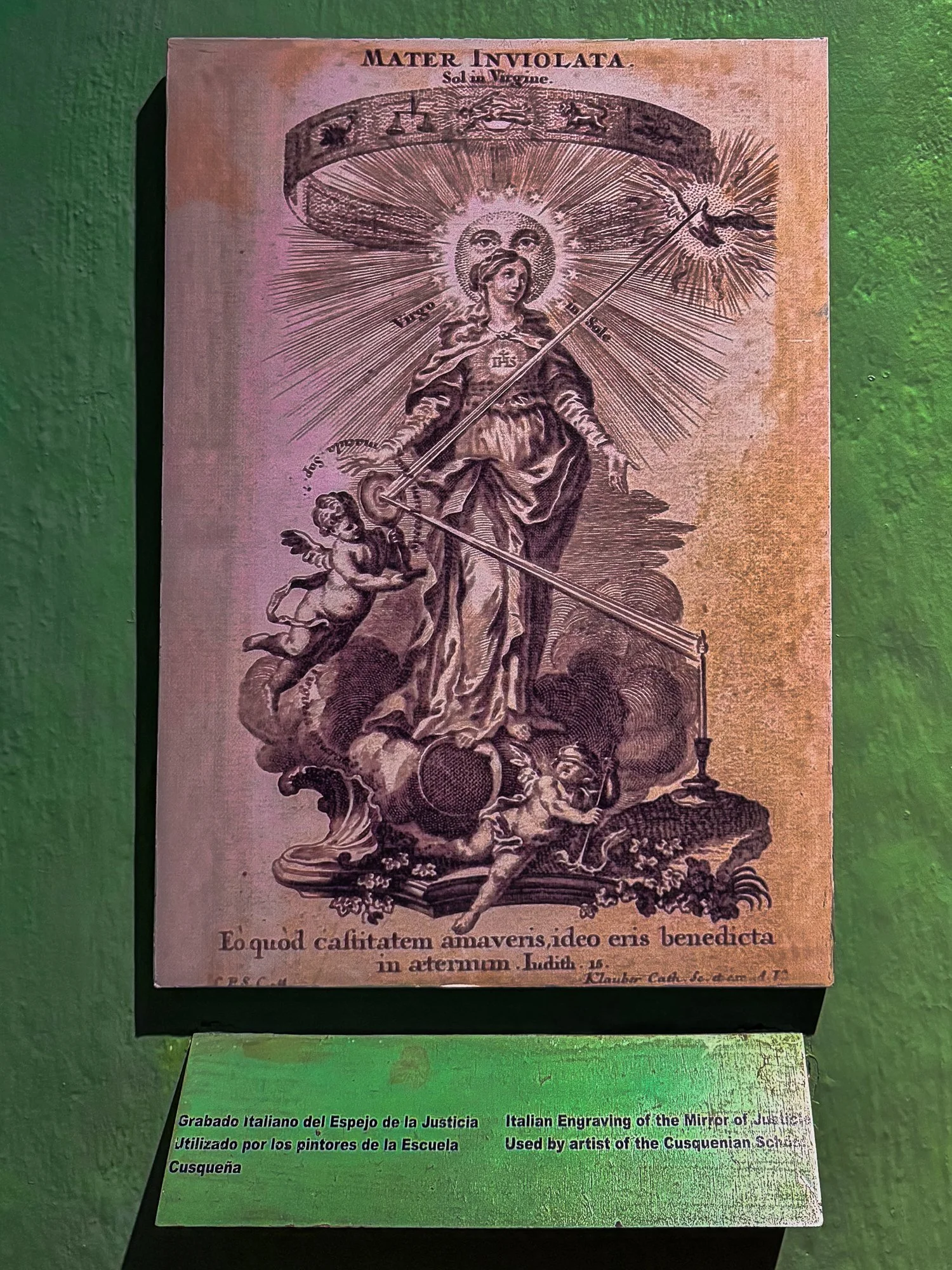

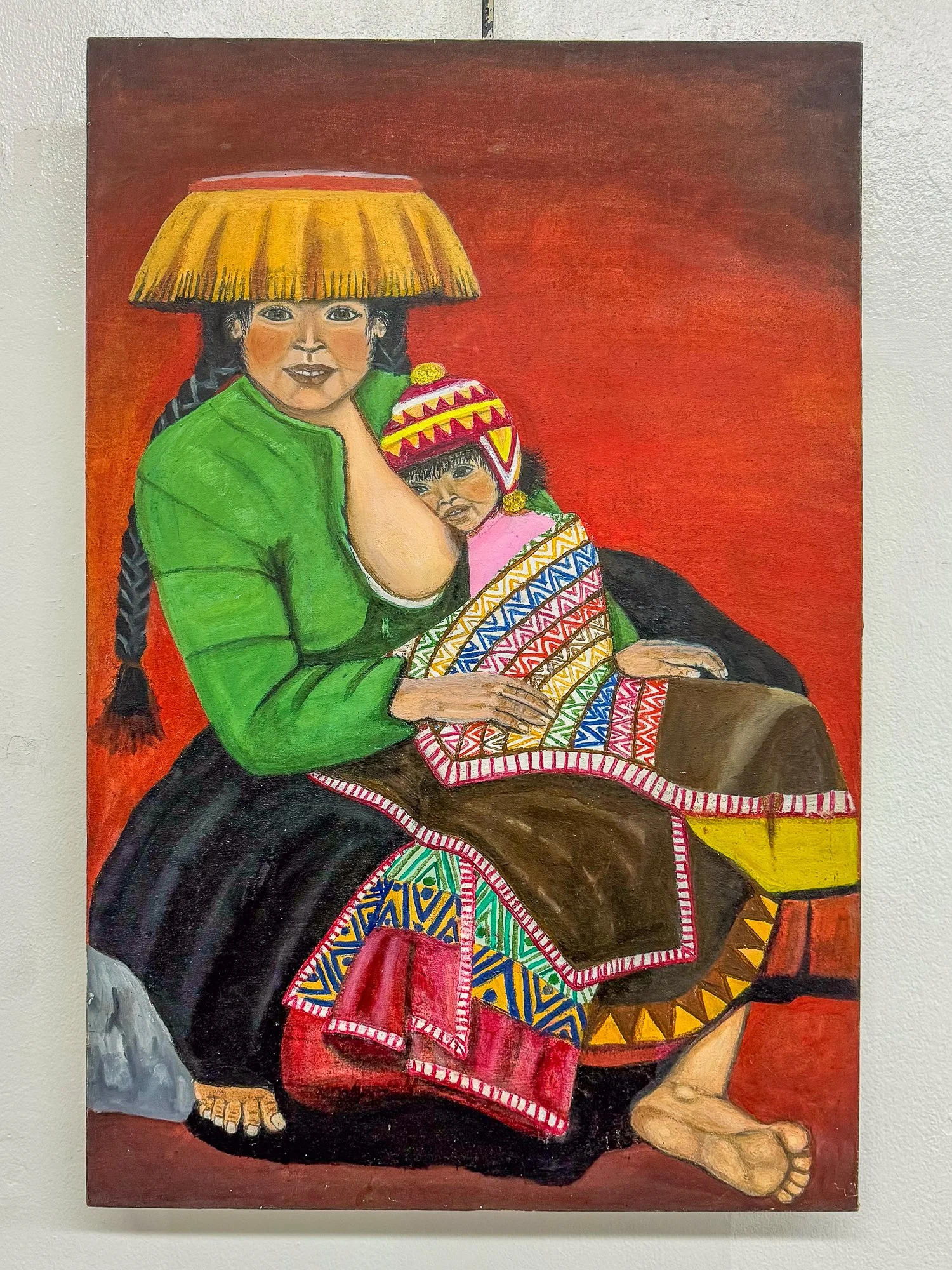

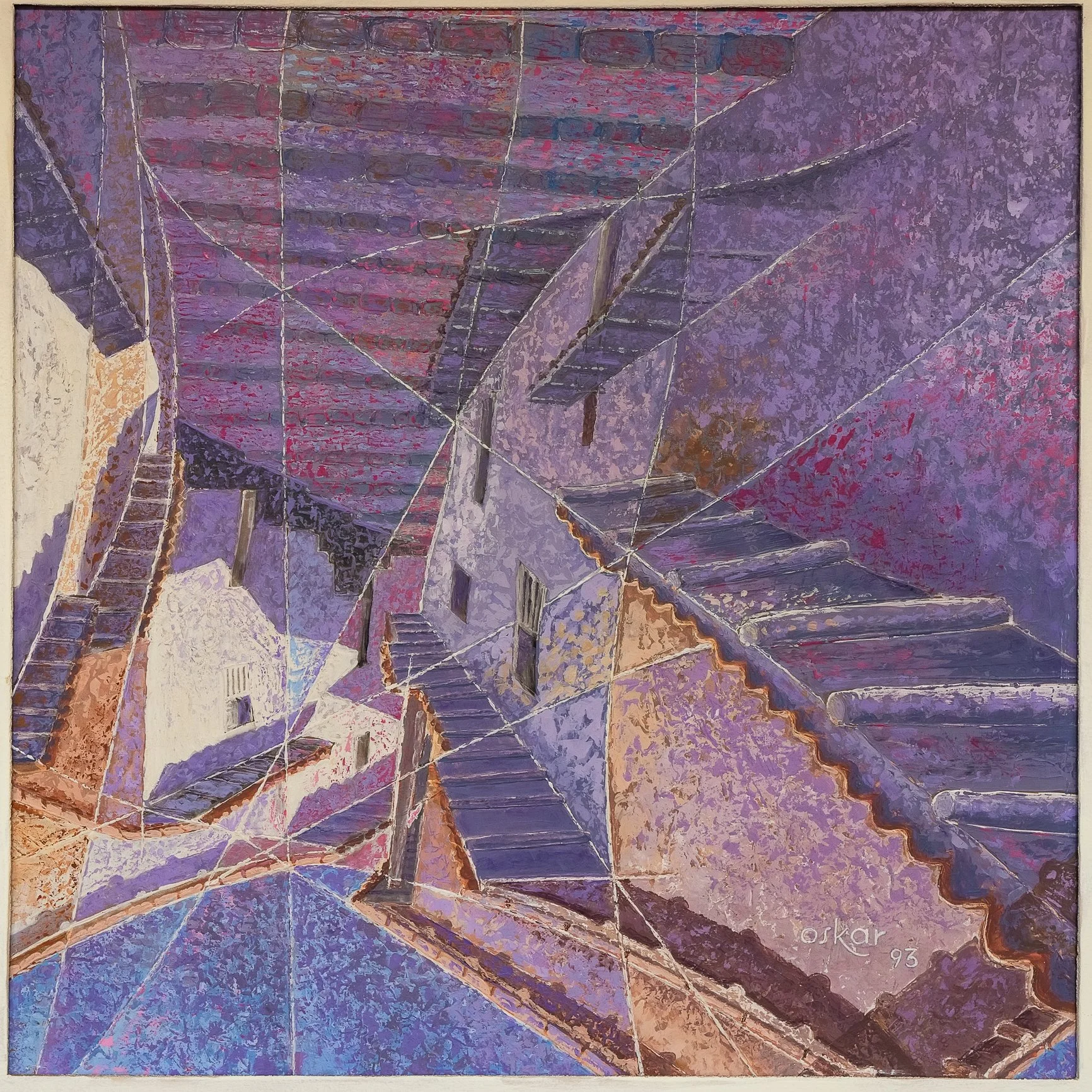

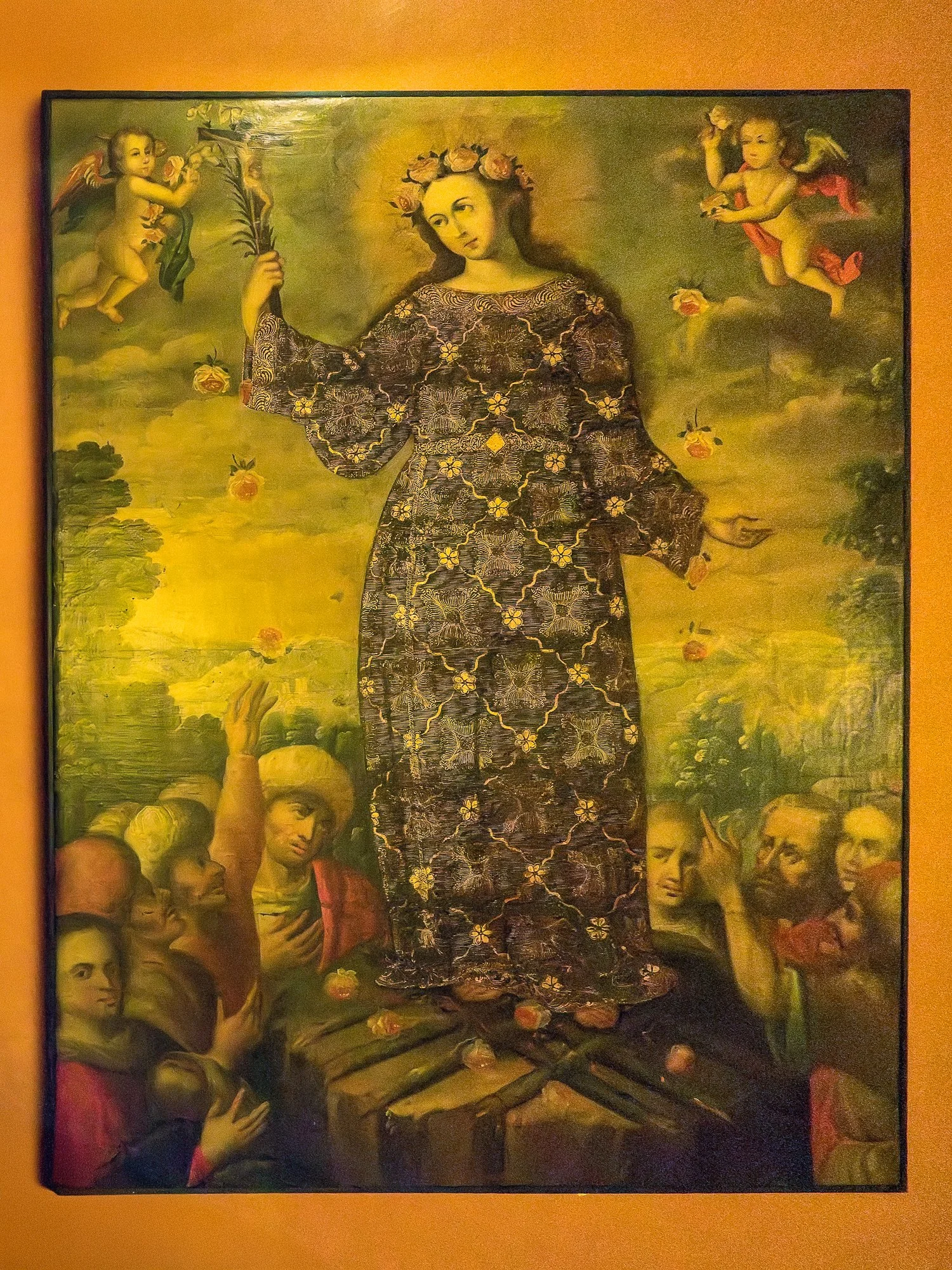

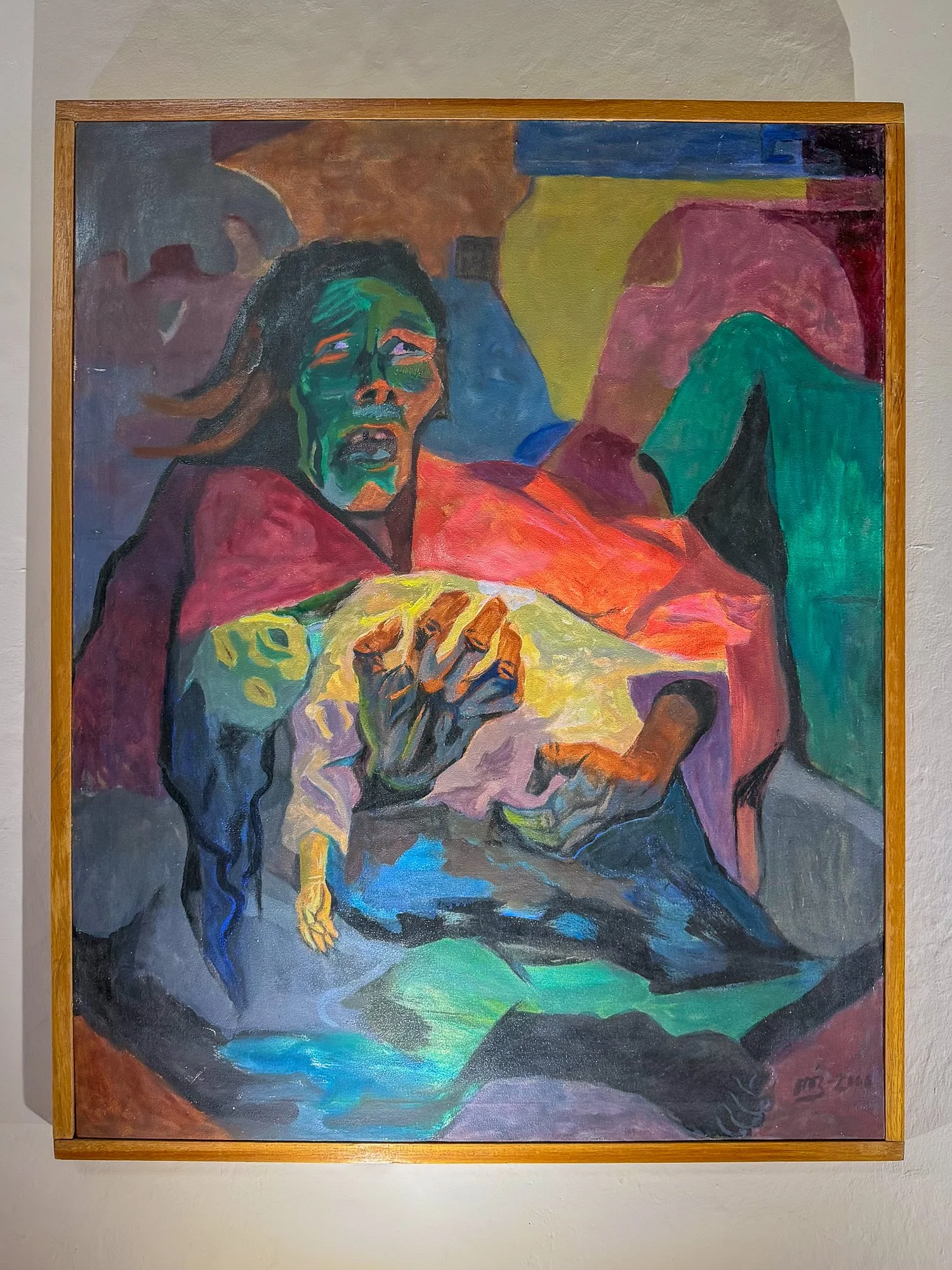

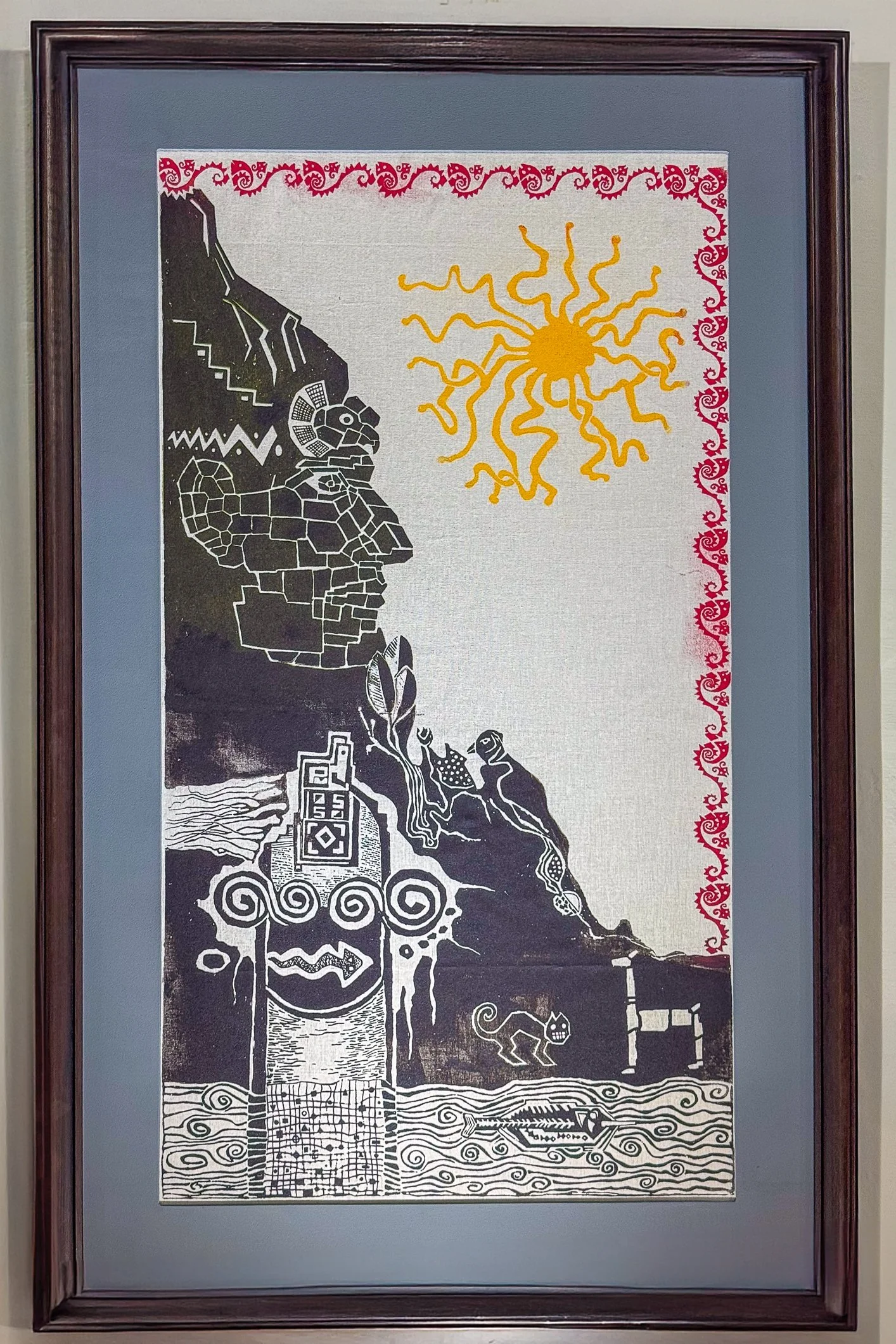

There is also a representation of the Cusco School of Art, a local painting tradition that blended Spanish styles with Andean influences. The artists were trained by Europeans but added their own touches — gold backgrounds, local plants, and of course also llamas in scenes from the Bible. Some works were copies of Italian paintings, but others had a totally unique vibe. Religious art was used as a major method for teaching and evangelising in the so-called “New World,” and the Cuzco School was a hub for this type of learning and art production. (Side note: ‘Cuzco’ with a ‘z’ is how the Spaniards spelled the city’s name).

Można też zobaczyć dzieła Szkoły Cuzco - lokalnej tradycji malarskiej, która łączyła hiszpańskie style z andyjskimi wpływami. Artyści byli szkoleni przez Europejczyków, ale dodawali własne elementy - złote tła, rodzime rośliny, a nawet lamy w scenach biblijnych. Niektóre prace to kopie włoskich obrazów, inne mają zupełnie unikalny charakter. Sztuka religijna była ważnym narzędziem nauczania i ewangelizacji w tzw. „Nowym Świecie”, a szkoła w Cuzco była centrum tej działalności. (Mała uwaga: „Cuzco” z „z” to hiszpańska pisownia nazwy miasta).

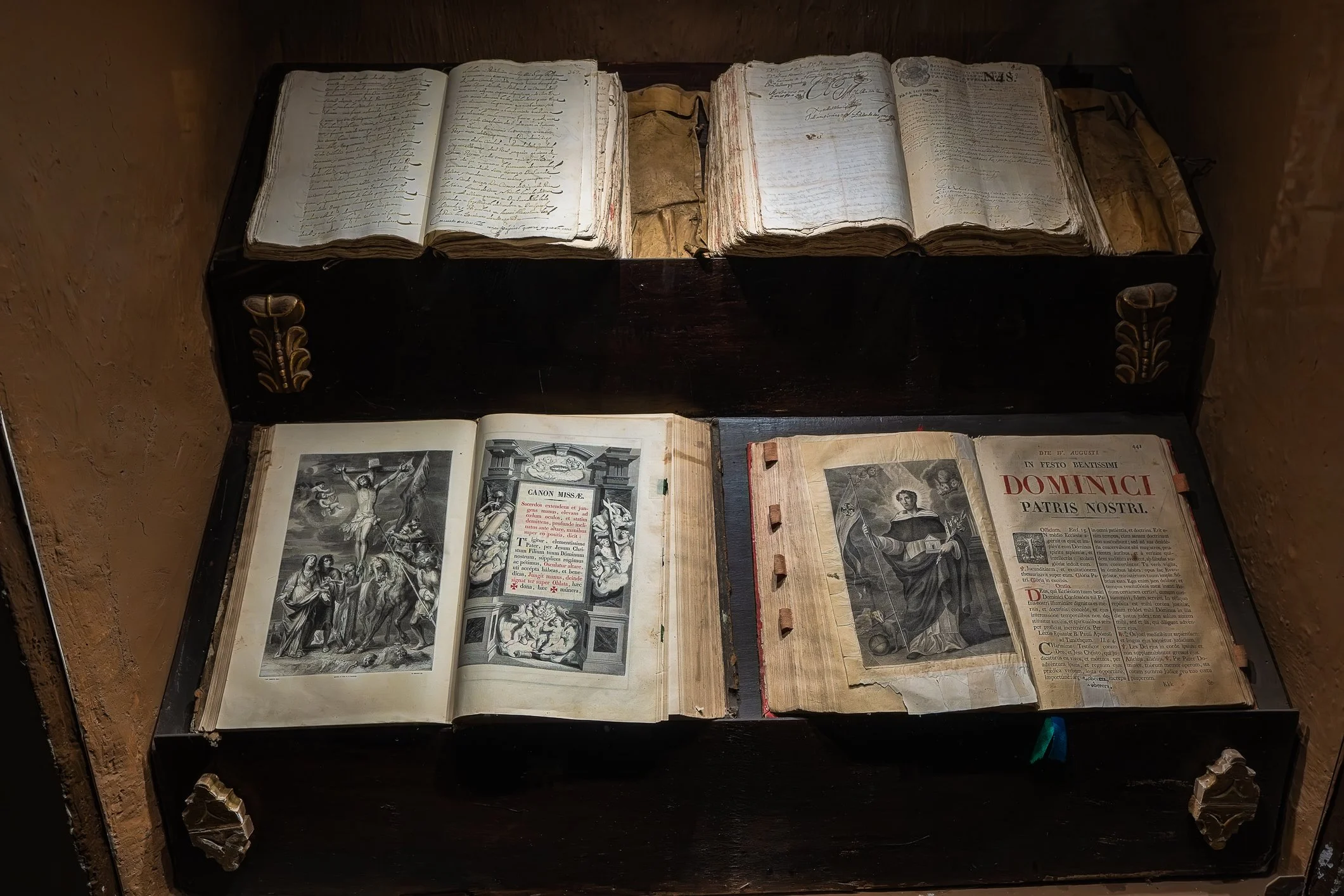

Period furniture is also featured, including a room devoted to the work of de la Vega. There is a life-sized sculpture of Garcilaso, plus early editions of his books. He was born in that very house in 1539, the son of an Inca princess and a Spanish conquistador.

W muzeum znajduje się także pokój z meblami z epoki oraz sala poświęcona de la Vedze. Jest tam rzeźba wielkości naturalnej przedstawiająca Garcilaso oraz pierwsze wydania jego książek. Urodził się właśnie w tym domu w 1539 roku jako syn inkaskiej księżniczki i hiszpańskiego konkwistadora.

Finally, one of the rooms focuses on Túpac Amaru II, the leader of a massive indigenous rebellion in 1780, his capture, trial, and eventual execution in Cusco’s Plaza de Armas.

Na koniec jedna z sal opowiada o Túpacu Amaru II (przywódcy powstania w 1780 roku), jego schwytaniu, procesie i ostatecznej egzekucji na Plaza de Armas w Cusco.