After breakfast, we head to Casa Concha, an 18th-century colonial mansion that now houses the Machu Picchu Museum. The house itself is worth a visit - it was built over Inca foundations and later belonged to José de Santiago Concha, a Spanish nobleman and colonial official. The architecture blends Spanish colonial style with elements of earlier Inca stonework, which is visible in some parts of the building. In a way, the house mirrors the story of Peru itself: layered with history, full of contrasts, and deeply rooted in both Inca and colonial pasts.

Outside, it features a stone facade from the Inca period that was later altered to include colonial-era doorways. Above the main entrance, a Baroque-style balcony with seven sections was added.

Po śniadaniu udajemy się do Casa Concha, kolonialnej rezydencji z XVIII wieku, w której dziś mieści się Muzeum Machu Picchu. Sama już willa jest warta zobaczenia - wybudowano ją na fundamentach inkaskiej budowli i należała m.in. do José de Santiago Concha, hiszpańskiego szlachcica i urzędnika kolonialnego (stąd nazwa miejsca). Architektura łączy styl hiszpańskiego kolonializmu z fragmentami kamiennej konstrukcji inków, które wciąż widać w niektórych częściach budynku. W pewnym sensie dom odzwierciedla historię Peru -jest pełen warstw, kontrastów i mocno zakorzeniony w obu tradycjach: inkaskiej i kolonialnej.

Na zewnątrz fasada wykorzystuje kamień z okresu inkaskiego, przerobiony później tak, by wbudować w niego późniejsze kolonialne drzwi. Nad drzwiami dodano także balkon w stylu barokowym, podzielony na siedem części.

The inner courtyard is quiet and open, with a two-level gallery running around it. The columns are stone, worn smooth, and the upper level on three sides is lined with simple arches that mirror the ones below. In the courtyard, there’s a small glass-covered section. Beneath it lies part of the original Inca flooring, about two meters below the current surface. Through the glass, we can see the perfectly cut stones, still tightly fitted together after centuries.

Dziedziniec wewnętrzny jest otoczony z trzech stron dwupoziomową galerią. Kolumny są kamienne, wygładzone czasem i użytkowaniem, a górny poziom, podobnie jak dolny, zdobią proste arkady. W jednym miejscu dziedzińca znajduje się mały przeszklony fragment. Pod nim widać część oryginalnej inkaskiej posadzki, około dwóch metrów poniżej obecnego poziomu. Przez szybę widać idealnie docięte kamienie, ciasno dopasowane i nieporuszone przez stulecia.

Inside the mansion, we spot patches of old mural paintings peeking out on stairways and upper-floor walls. These are colonial-era frescoes, uncovered during restoration and originally painted in the late 1700s. They show flowers, birds, fruit, and religious figures like San Cristóbal and San Miguel Arcángel.

Na ścianach przy schodach oraz na górnych kondygnacjach dostrzegamy fragmenty starych fresków. Są to polichromie kolonialne, odsłonięte podczas renowacji, pierwotnie namalowane pod koniec XVIII wieku. Przedstawiają kwiaty, ptaki, owoce oraz postaci świętych, jak Św. Krzysztof, czy Archanioł Michał.

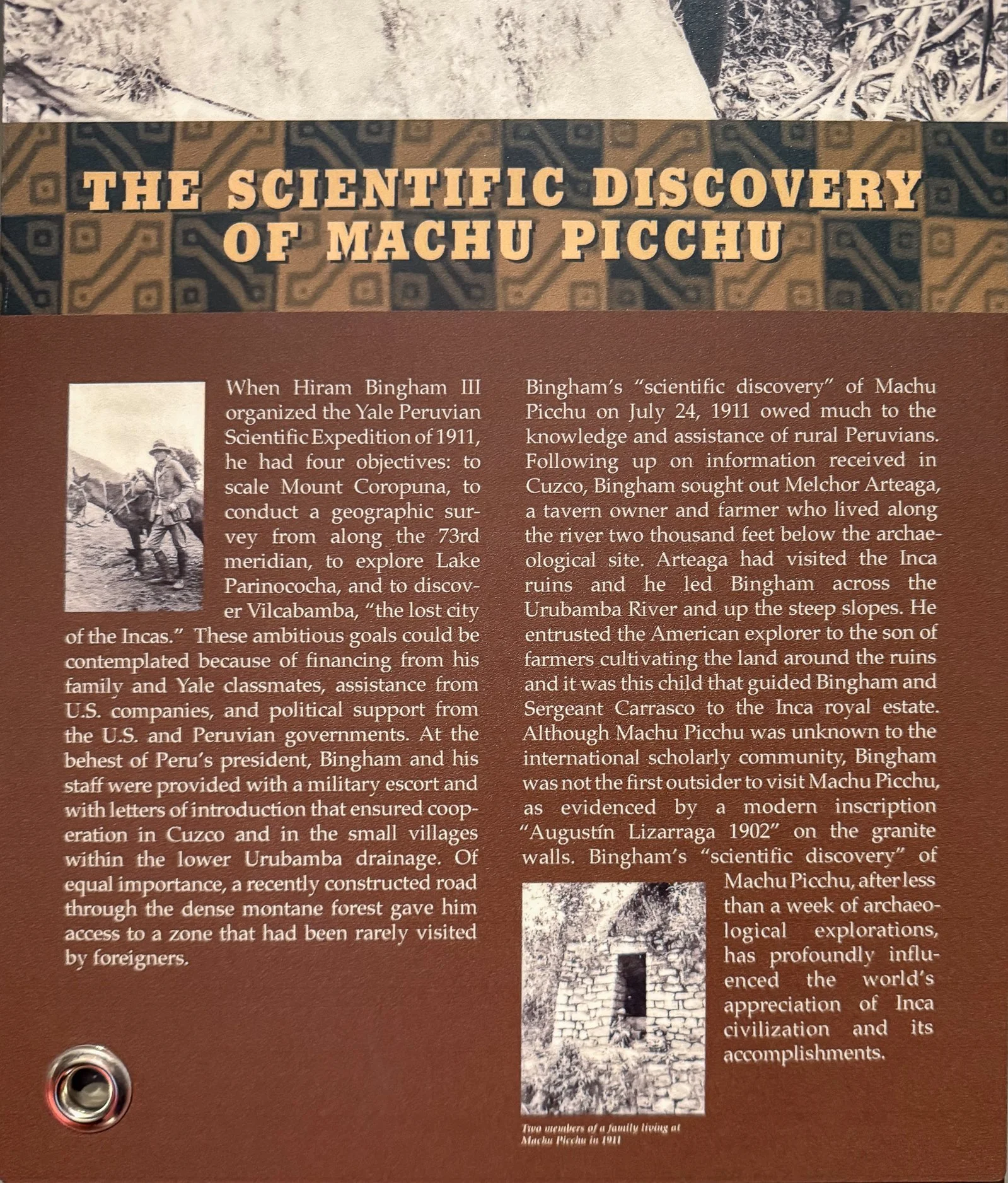

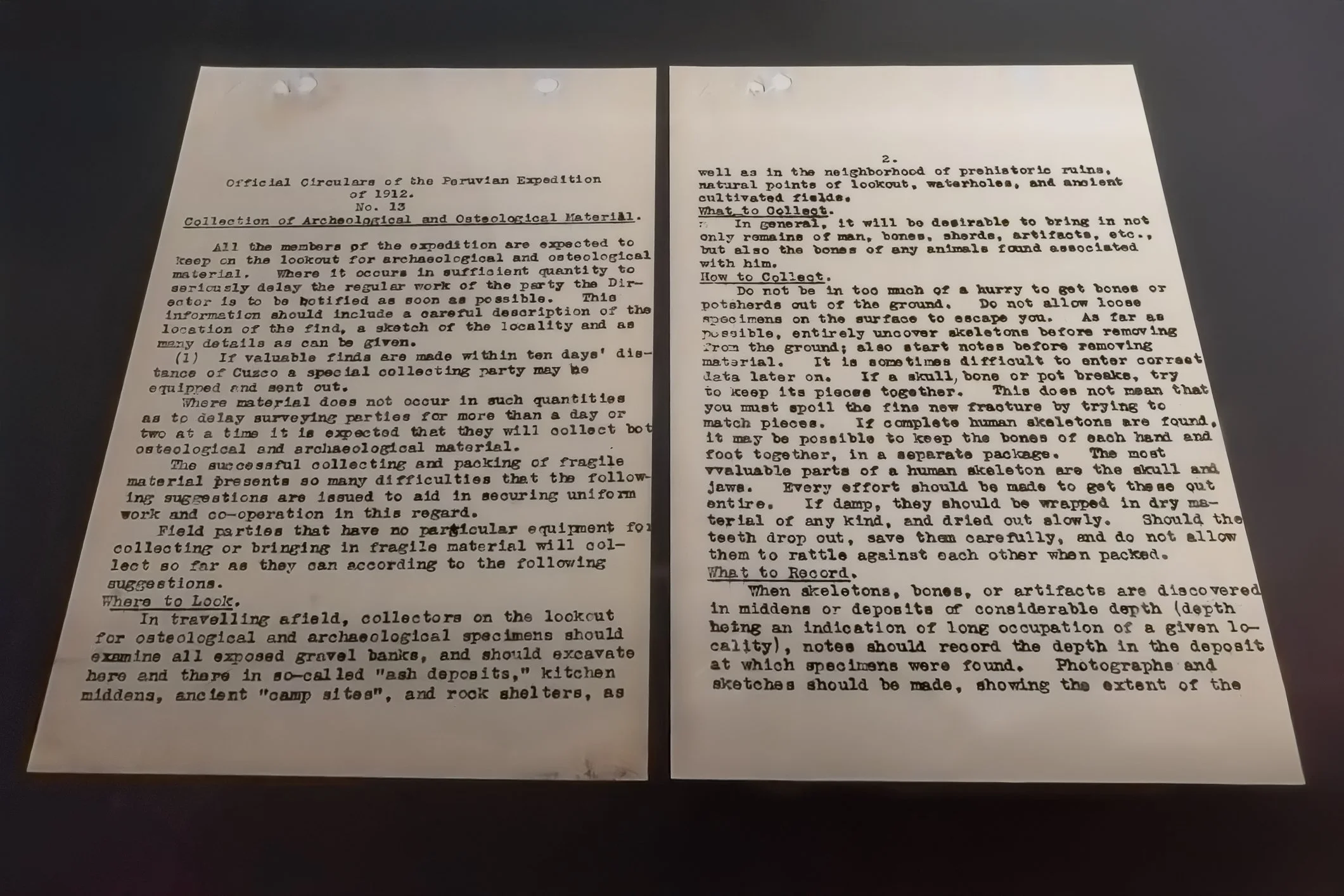

The museum holds over 360 artefacts that Hiram Bingham took back to Yale in 1912 for study and which were finally returned to Peru in 2011, including some early photographs. Despite what many think, Bingham didn’t actually “discover” Machu Picchu. Local people had always known about it and guided him to the site. He wasn’t even the first European to visit. Still, he was the one who put Machu Picchu on the world map making it popular.

The museum also has in its possession a collection from San Antonio Abad University from more recent excavations.

Muzeum przechowuje ponad 360 artefaktów, które Hiram Bingham zabrał do Yale w 1912 roku na badania i które ostatecznie wróciły do Peru w 2011 roku, łącznie z wczesnymi fotografiami. Wbrew powszechnemu przekonaniu, Bingham nie „odkrył” Machu Picchu. Lokalni ludzie zawsze wiedzieli o tym miejscu i to oni zaprowadzili go do ruin. Nie był on nawet pierwszym Europejczykiem, który tam trafił (o czym mówią nawet jego własne zapiski). To on jednak sprawił, że świat na serio zainteresował się Machu Picchu.

Muzeum posiada również znaleziska z prac archeologicznych prowadzonych przez Uniwersytet San Antonio Abad.

As we move through the museum, it’s clear how central religion was to Inca life. The Incas worshipped many gods: Wiracocha, the creator; Inti, the sun god; Mamaquilla, the moon goddess; Illapa, the thunder god; and Pacha Mama, mother Earth. But their beliefs went beyond these major gods. Spirits lived in rivers, rocks, mountains, and ancestors - these were called huacas and could be found all around Cusco. To keep good relations with these spirits, people made offerings and held rituals. Many of the ceramics, textiles, and weapons on display were made as gifts to these gods.

The museum explains how Inca religious life followed two calendars—one based on the sun’s yearly path, the other on the cycles of the moon and stars. Ceremonies were carefully timed with these calendars, blending the everyday with the sacred.

W muzeum Machu Picchu wyraźnie widać, jak bardzo religia przenikała życie Inków. Wierzyli oni w wielu bogów: Wirakoczę (boga stwórcę), Inti (boga słońca), Mamaquillę (boginię księżyca), Illapę (boga grzmotu) i Pacza Mamę (matkę Ziemię). Ale wiara sięgała też dalej, obejmując duchy rzek, gór, kamieni, czy przodków. Te święte miejsca i duchy nazywano huacas i były one rozsiane po całym terenie Cusco. Aby utrzymać z nimi harmonię, składano im ofiary i przestrzegano różnych rytuałów. Wiele ceramiki, tkanin i broni, które wchodzą w skład ekspozycji muzeum powstało właśnie jako ofiary dla bóstw.

Muzeum pokazuje także, jak życie religijne Inków podporządkowane było dwóm kalendarzom - jeden oparty na cyklu rocznym Słońca, drugi na cyklach Księżyca i gwiazd. Ceremonie planowano zgodnie z tymi cyklami, łącząc życie codzienne ze światem sacrum.

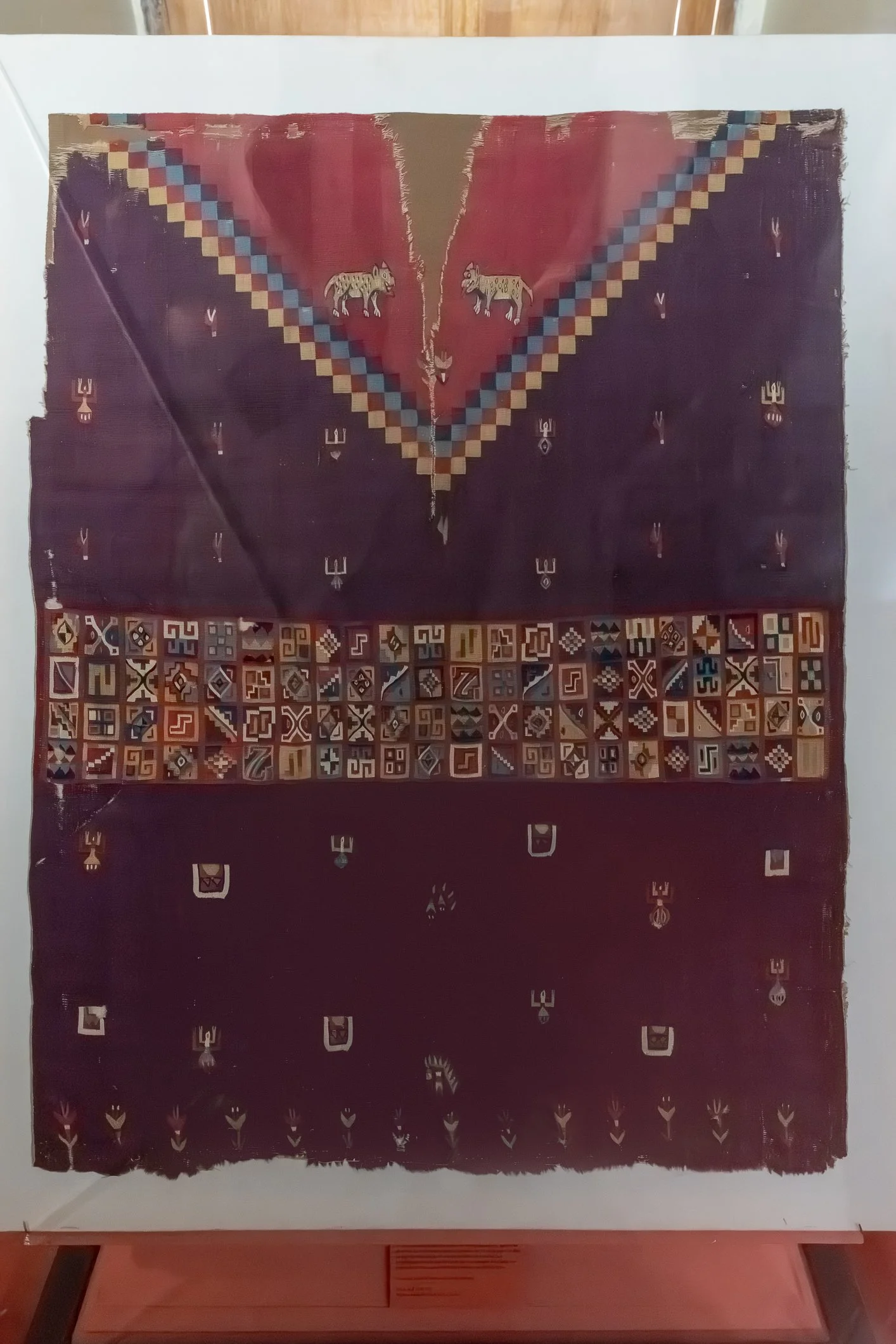

One thing that stood out was the importance of textiles. These were often prized more than gold or silver. The finest cloth, called cumbi, was made from alpaca wool and cotton. Clothing wasn’t just practical; it was a symbol of status. The Sapa Inca (the ruler) and his inner circle wore tunics decorated with geometric designs called tocapu, often crafted from rare vicuña wool.

Jedna rzecz szczególnie przykuwa uwagę - znaczenie tkanin. Były często cenione wyżej niż złoto albo srebro. Najlepszy materiał wytwarzano z wełny alpaki i bawełny. Ubrania miały nie tylko funkcję praktyczną, ale także symbolizowały status. Sapa Inka (przywódca) i jego najbliższe otoczenie nosili tuniki ozdobione geometrycznymi wzorami zwanymi tokapu, często tkanymi z rzadkiej wełny wikunii.

We also learned about the quipu—a system of knotted strings made from cotton or camelid fibre, used for keeping records. “Quipu” means “knot” in Quechua. Different colours, types of knots, string direction, and placement all carried meaning. Incas used it to track numbers in a decimal system - a pretty advanced form of bookkeeping without writing.

Poznaliśmy też quipu — system supełkowych nici z włókna bawełnianego lub z lamy, który służył do „zapisywania” informacji. „Quipu” w języku keczua oznacza „supeł”. Kolor, kierunek utkania i miejsce położenia włókna, oraz rodzaj supełka, przekazywały konkretne znaczenie. Inkowie wykorzystywali tu system dziesiętny liczenia i zapisywali supełkowo nawet zaawansowane informacje.

There’s also a detailed model of Machu Picchu itself, similarly like in Museo Inka, but to be honest, we fully understood it only after visiting Machu Picchu.

W muzeum znajduje się także szczegółowa makieta Machu Picchu, podobna do tej, którą widzieliśmy w Museo Inka, chociaż tak w pełni zrozumieliśmy ją dopiero po wizycie w cytadeli.

The museum also shares findings from studies of bones found in burial caves at Machu Picchu. These show that people there ate a lot of maize – sometimes it constituted up to 65% of their diet. The bone and teeth analyses suggest their lives weren’t especially harsh or violent, though some did suffer illnesses like tuberculosis and iron-deficiency anaemia.

One striking feature of Inca-era skeletons is head shaping. In many parts of South America, including Machu Picchu, babies’ heads were wrapped with cloth or bound with boards to intentionally reshape their skulls. This practice was banned by Spanish authorities in 1585 and again in 1752. Because infant skulls are soft and malleable, reshaping was relatively easy and did not damage the brain. At Machu Picchu, both intentional and accidental skull shaping has been found. The intentional kind was commonly known as “Aymara-style.” It involved shaping the skull to create an elongated, often slightly flattened head.

Muzeum pokazuje również wyniki badań kości z grobowców Machu Picchu. Wynika z nich, że w diecie mieszkańców przeważała kukurydza — czasem stanowiła nawet 65% ich pożywienia. Analizy zębów i kości sugerują, że życie nie było tam wyjątkowo trudne ani pełne przemocy, choć zdarzały się choroby jak gruźlica czy anemia z niedoboru żelaza.

Jedną z bardziej zaskakujących praktyk było formowanie głowy. U niemowląt owijało się głowy ciasno materiałem lub używano specjalnych deseczek, by celowo zmienić kształt czaszki. Praktykę tę zakazali Hiszpanie w latach 1585 i potem jeszcze raz w1752. Ponieważ czaszki dzieci są miękkie, zmiany kształtu głowy były łatwe do osiągnięcia i zwykle bezpieczne. W szczątkach z Machu Picchu znaleziono zarówno celowe, jak i przypadkowe deformacje. Te celowe zwykle były w stylu zwanym „Aymara”, gdzie czaszki były wydłużone i lekko spłaszczone.

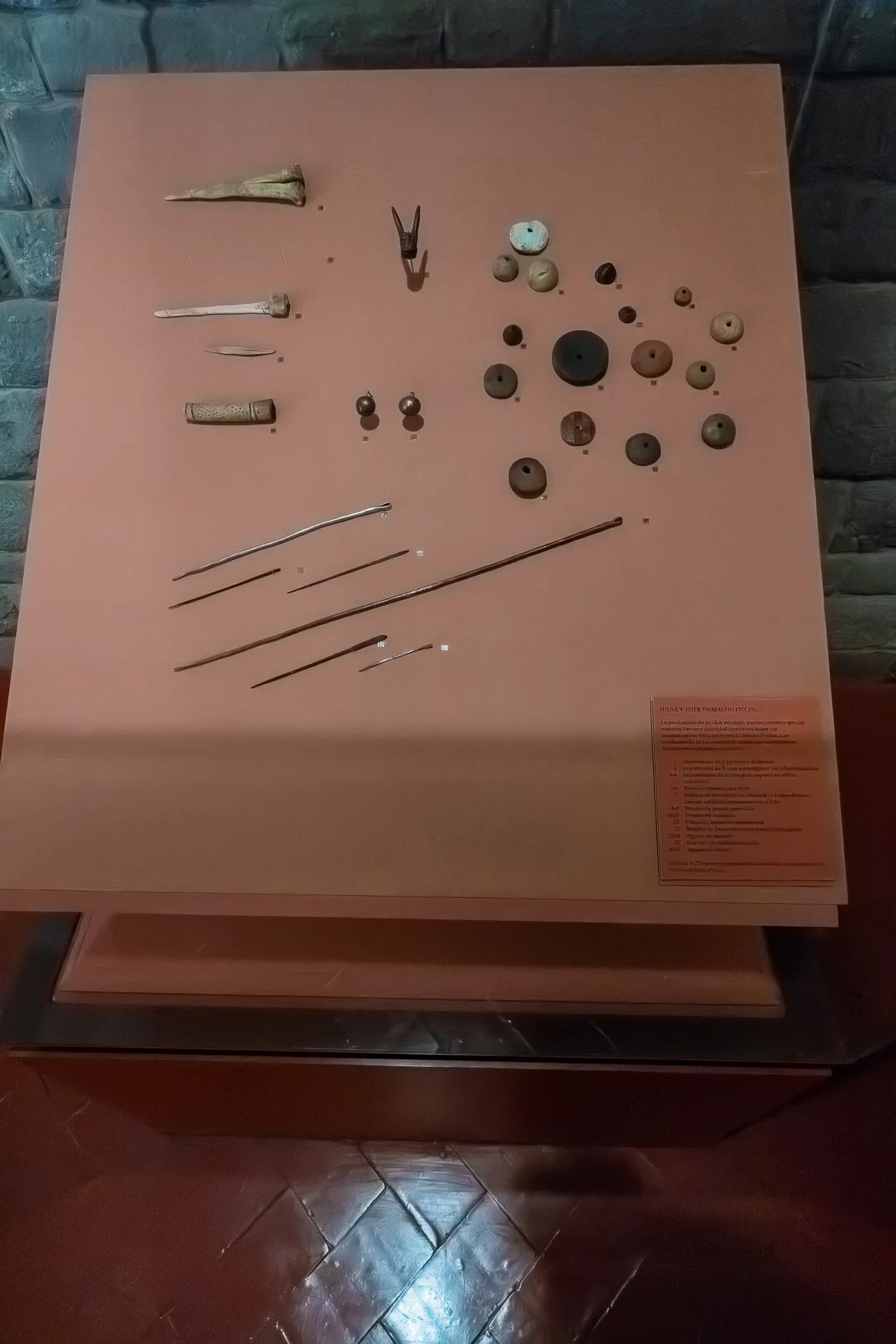

Metalwork was another important activity in Machu Picchu. Archaeologists found raw metal, unfinished pieces, waste from the production process, and the tools used to make them. Most of the metal objects were made from tin bronze (an alloy of copper), but gold and silver were used too.

One museum scene shows a metalworker hammering a rough silver nugget into a thin sheet using a polished stone.

Obróbka metalu była ważnym elementem życia w Machu Picchu. Archeolodzy odkryli surowiec, niedokończone przedmioty, odpady produkcyjne i narzędzia. Większość wyrobów była z brązu cyny (stop miedzi), ale wykorzystywano też złoto i srebro.

W jednej z ekspozycji widać rzemieślnika, uderzającego srebrną bryłkę wygładzonym kamieniem, by zrobić z niej cienką blaszkę.

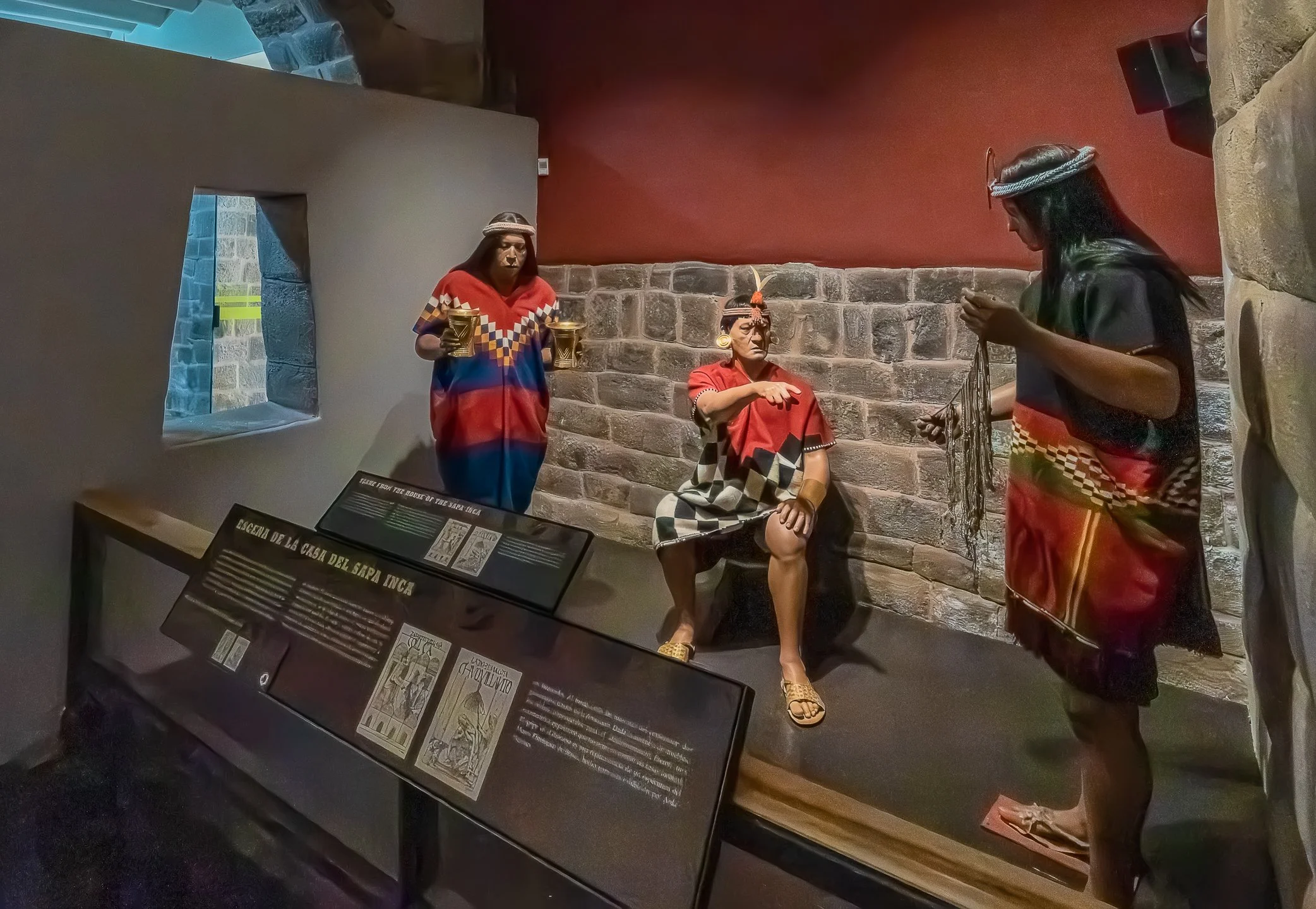

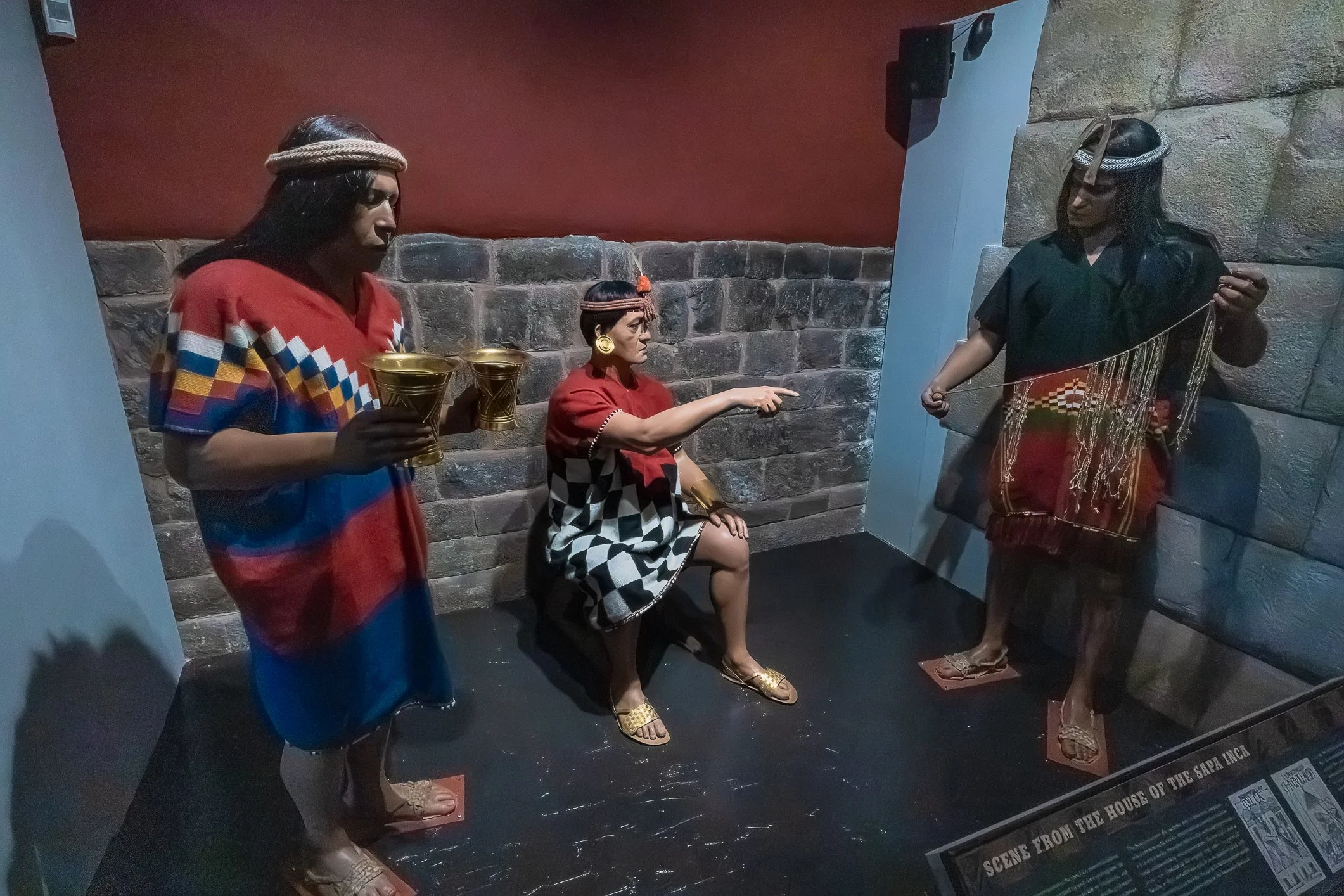

In another display, the Sapa Inca (the ruler) is shown receiving an official who holds a quipu. The ruler wears the traditional headdress called a mascaypacha, along with a fine tunic made of alpaca wool. His rank is also shown by gold sandals and large gold ear ornaments. A servant nearby holds gold beakers filled with chicha, the traditional corn beer.

Inna scena przedstawia Sapa Inkę, który przyjmuje urzędnika trzymającego quipu. Władca nosi maskalpacz, tradycyjną ozdobę głowy, oraz ozdobną tunikę z alpaki. Jego status podkreślają złote sandały i duże złote kolczyki. Obok stoi służący ze złotymi kubkami napełnionymi chichą, tradycyjnym piwem z kukurydzy.

Finally, the museum highlights the mallki - royal mummies who were revered as living ancestors. They were sacred, treated like living ancestors, and brought out during major celebrations like Capac Raymi, Inti Raymi, and Huarachico. To the Incas, death wasn’t the end. Ancestors remained an active part of the community, and their presence was honoured regularly.

Na koniec muzeum pokazuje mallki, królewskie mumie, które traktowano jak żywych przodków. Były one obecne i czczone podczas głównych uroczystości: Capac Raymi, Inti Raymi, czy Huarachico. Dla Inków śmierć nie była bowiem końcem. Przodkowie pozostawali integralną częścią społeczności i byli regularnie honorowani.

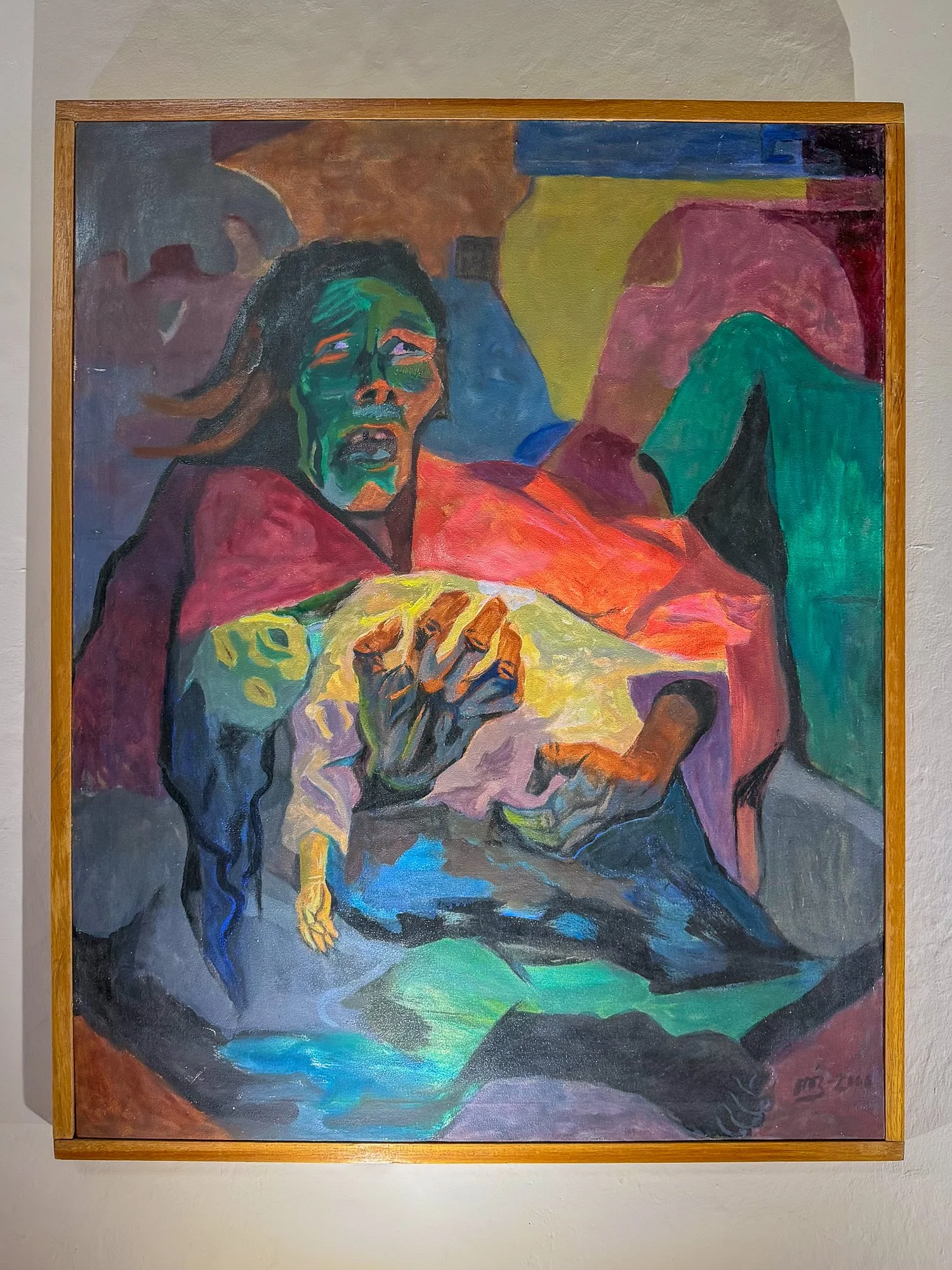

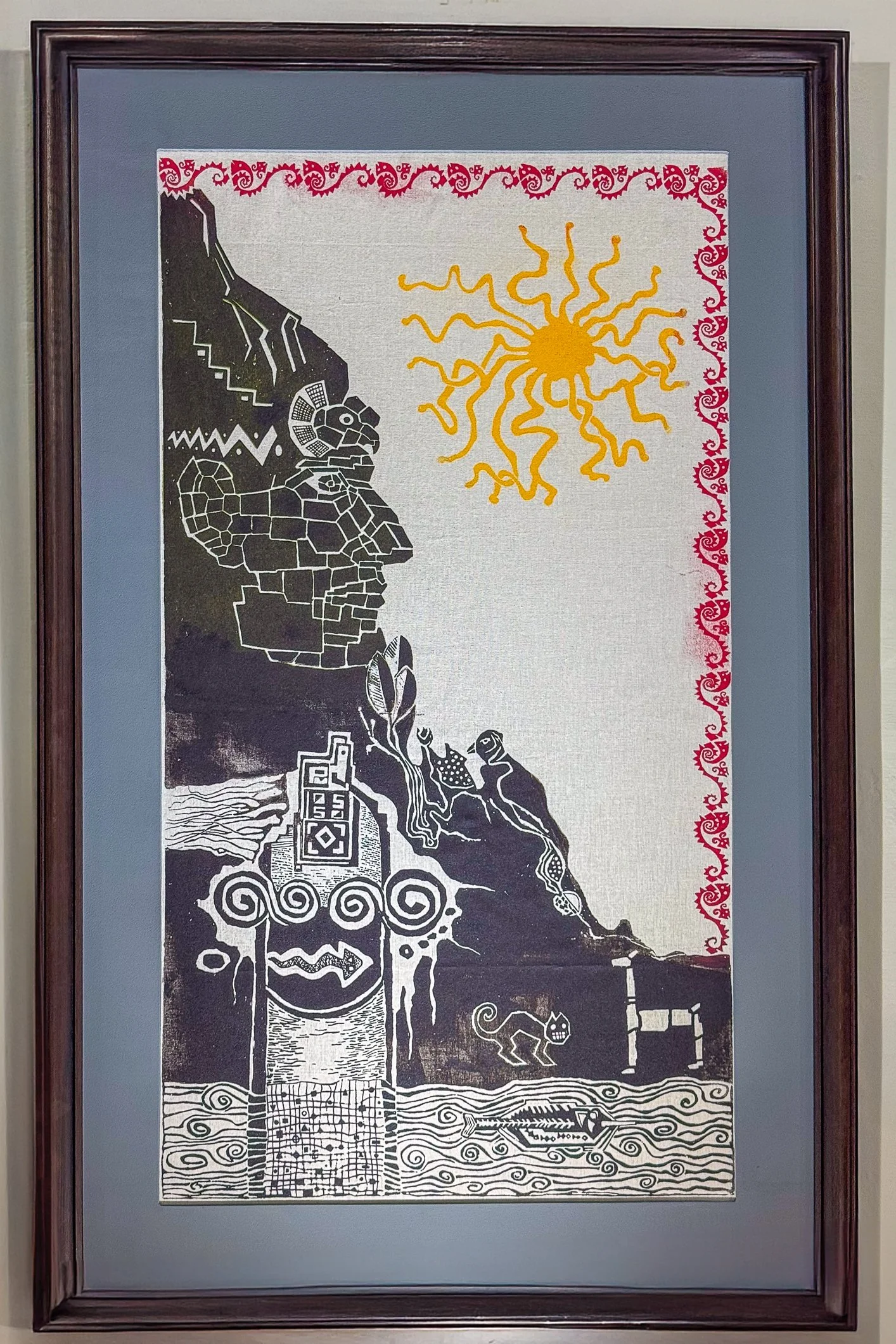

Apart from the permanent expositions, on the second floor of Casa Concha, we found a temporary gallery space. It turned out to be the IV Salón de Artes Visuales, organized by UNSAAC together with the Universidad del Arte Diego Quispe Tito, presented at the museum during their anniversary celebrations.

Oprocz stałych ekspozycji muzeum, na drugim piętrze natrafiliśmy na wystawę tymczasową. Był to „IV Salón de Artes Visuales”, organizowany przez UNSAAC wraz z Universidad del Arte Diego Quispe Tito.