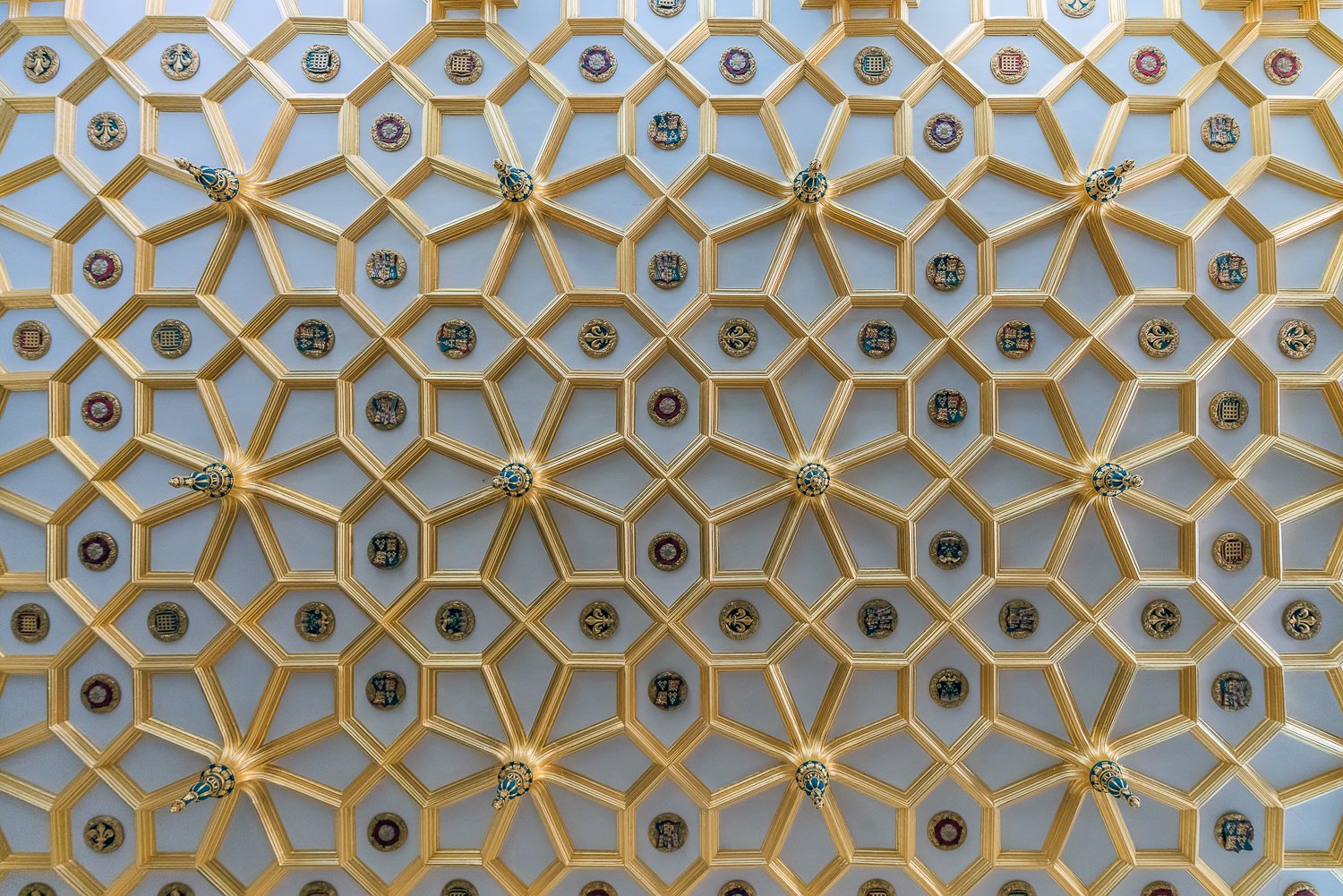

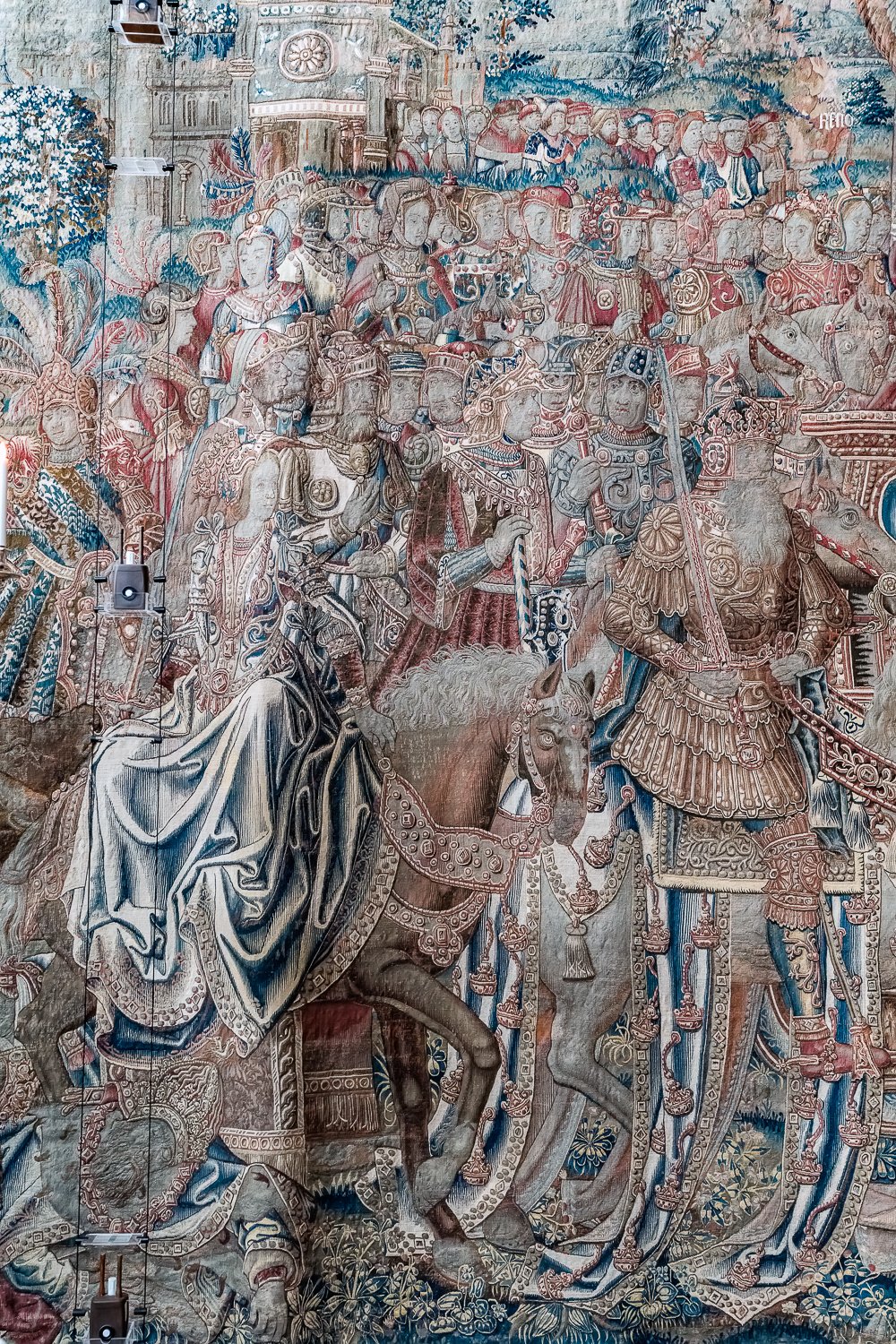

The Bahia Palace is a stunning example of Moroccan architecture combining Moorish, Arab, and Islamic styles. Arches, domes, intricate plasterwork and zouak (painted wood) adorn the architecture adding to the palace's grandeur.

As in typical Islamic architecture, the palace is marked by bold geometrical symmetry in all its shapes, and landscaped gardens with their reflected light and water features. However, within the Bahia Palace, there are instances where the fundamental rules and principles of Islamic architecture are deviated from. For example, the distribution of living areas and courtyards is uneven. This can be attributed to the palace's complex history, as its expansion necessitated accommodating existing buildings within a limited space.

Nasz drugi riad znajduje się zaledwie kilka kroków od Pałacu Bahia.

Zbudowany w XIX wieku przez Si Moussę, wielkiego wezyra sułtana, na jego własny użytek, pałac przeszedł na przestrzeni lat kilka procesów renowacji, ale nadal daje wgląd w swój pierwotny urok i wielkość. Jest to wspaniały przykład architektury marokańskiej łączącej style mauretańskie, arabskie i islamskie. Łuki, kopuły, misterne stucco i zouak (malowane drewno) dodają pałacowi majestatu. Typowo dla architektury islamskiej, pałac charakteryzuje się geometryczną symetrią kształtów oraz pięknymi ogrodami, wykorzystaniem odbitego światła i elementami wody. Jednak zdarzają się tu przypadki odstępstwa od podstawowych zasad i zasad architektury islamskiej. Na przykład rozkład obszarów mieszkalnych i dziedzińców jest nierówny. Można to przypisać złożonej historii pałacu, gdyż jego rozbudowa wymagała oddawania budynków na ograniczonej przestrzeni.

Na teren pałacu wchodzi się przez łukowatą bramę od głównej ulicy, za którą do pałacu prowadzi długa ogrodowa ścieżka. Ścieżka między zewnętrznymi ścianami pałacu a wejściem do samego pałacu Bahia jest wysadzana palmami, jukami, drzewami cytrusowymi, cyprysami i hibiskusami.

Pierwszym budynkiem, do którego wchodzimy podczas naszej wizyty jest Mały Riad (Petit Riad). Jego kwadratowy ogród wypełniony jest bujną roślinnością i podzielony chodnikami wzdłuż dwóch środkowych osi. Otaczają go bogato zdobione galerie i pokoje. Podziwiać możemy tu kunsztowne dekoracje ze sztukaterii i drewna cedrowego.

From here we go to the Small Courtyard, with white, mostly unadorned walls. The floor consists of white Carrara marble. In the centre stands a fountain, encircled by tiled mosaics. These tiny, carefully positioned ceramics are particularly characteristic of Morocco. The technical term for this art is Zellij. Four rooms open out onto the courtyard: each was once occupied by one of the four wives of the Grand Vizier. The buildings in this part of the palace are more modestly decorated than the two riads. Other than the mosaics, the notable features are the cedarwood ceilings and the beautifully carved doors.

Stąd idziemy na Mały Dziedziniec, z białymi, w większości pozbawionymi ozdób ścianami. Podłoga wykonana jest z białego marmuru z Carrary. Pośrodku stoi fontanna otoczona mozaikami kafelkowymi. Te maleńkie, starannie rozmieszczone ceramiki są szczególnie charakterystyczne dla Maroka. Termin techniczny określający tą sztukę to Zellij. Cztery pokoje wychodzą na ten dziedziniec. Każdy z nich był kiedyś zajmowany przez jedną z czterech żon wielkiego wezyra. Budynki w tej części pałacu są skromniej urządzone niż w riadach. Oprócz mozaik godnymi uwagi elementami są sufity z drewna cedrowego i pięknie rzeźbione drzwi.

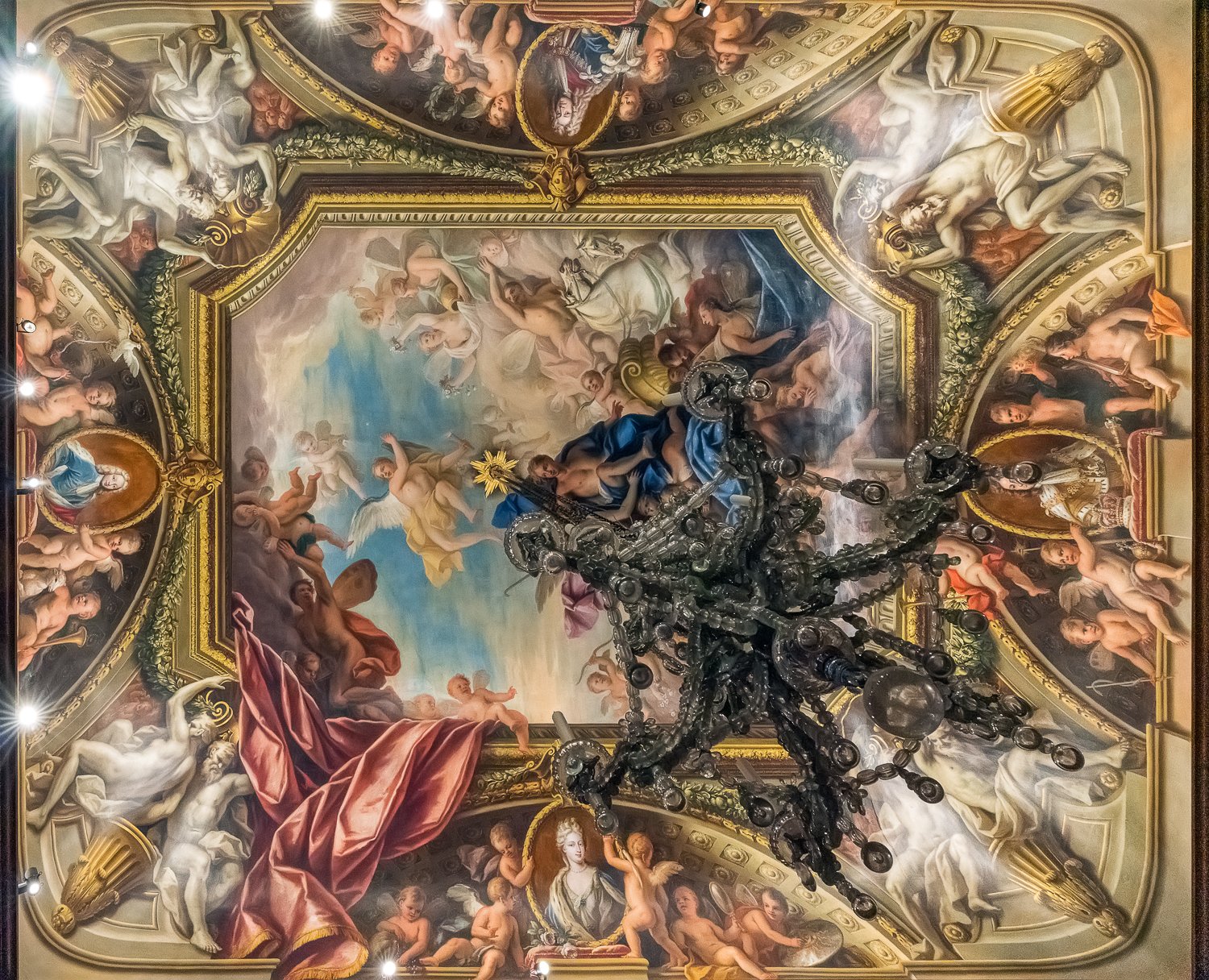

The so-called Courtyard of Honour (Cour d’honneur) or Grand Court, is particularly impressive. It was completed in 1898/99 and its size is really impressive (50 by 30 metres). The courtyard is completely lined with Italian Carrara marble and surrounded by an elegant and colourful wooden gallery. It is surrounded by as many as 80 rooms, built to house the concubines of the Grand Vizier’s harem. These women did not enjoy a particularly high social status during their time, nor did the eunuchs who guarded the harem.

Dziedziniec Honorowy (Cour d’honneur), znany także jako Wielki Dziedziniec został ukończony w latach 1898/99, a jego wymiary są naprawdę imponujące (50 na 30 metrów). Jest on w całości wyłożony marmurem i otoczony elegancką, kolorową drewnianą galerią. Otacza go aż 80 pokoi, zbudowanych dla konkubin haremu wielkiego wezyra. Kobiety te nie cieszyły się w swoich czasach szczególnie wysokim statusem społecznym, podobnie jak eunuchowie strzegący haremu.

The Large Riad is located on the northern side of the Courtyard of Honour. This is the oldest part of the Bahia Palace. The ceilings are carved from cedar wood and embellished with decorative patterns. The courtyard is occupied by a very large riad garden which is still planted with trees from the 19th century.

Wielki Riad położony jest po północnej stronie Dziedzińca Honorowego. To najstarsza część Pałacu Bahia. Sufity są tu rzeźbione z drewna cedrowego i ozdobione dekoracyjnymi wzorami. Dziedziniec zajmuje bardzo duży ogród, w którym nadal rosną drzewa z XIX wieku.

To the west and east of the Large Riad, there are additional chambers, which are equipped with fireplaces and adorned in the typical Zellij style. Once again, the wooden ceilings are beautifully painted. Near the palace gates, there is a private apartment. This was constructed in 1898 for Bou Ahmed's first wife, Lala Zinabe. In this space, too, there are masterfully painted ceilings, elaborate stucco decorations, and stained-glass windows.

Na zachód i wschód od Wielkiego Riadu znajdują się dodatkowe komnaty wyposażone w kominki i ozdobione typowym stylem Zellij. Po raz kolejny drewniane sufity są pięknie pomalowane. Niedaleko bram pałacowych znajduje się prywatny apartament. Został on zbudowany w 1898 roku dla pierwszej żony Bou Ahmeda, Lali Zinabe. Również i w tej przestrzeni znajdują się mistrzowsko pomalowane sufity, wyszukane dekoracje sztukatorskie i witraże.