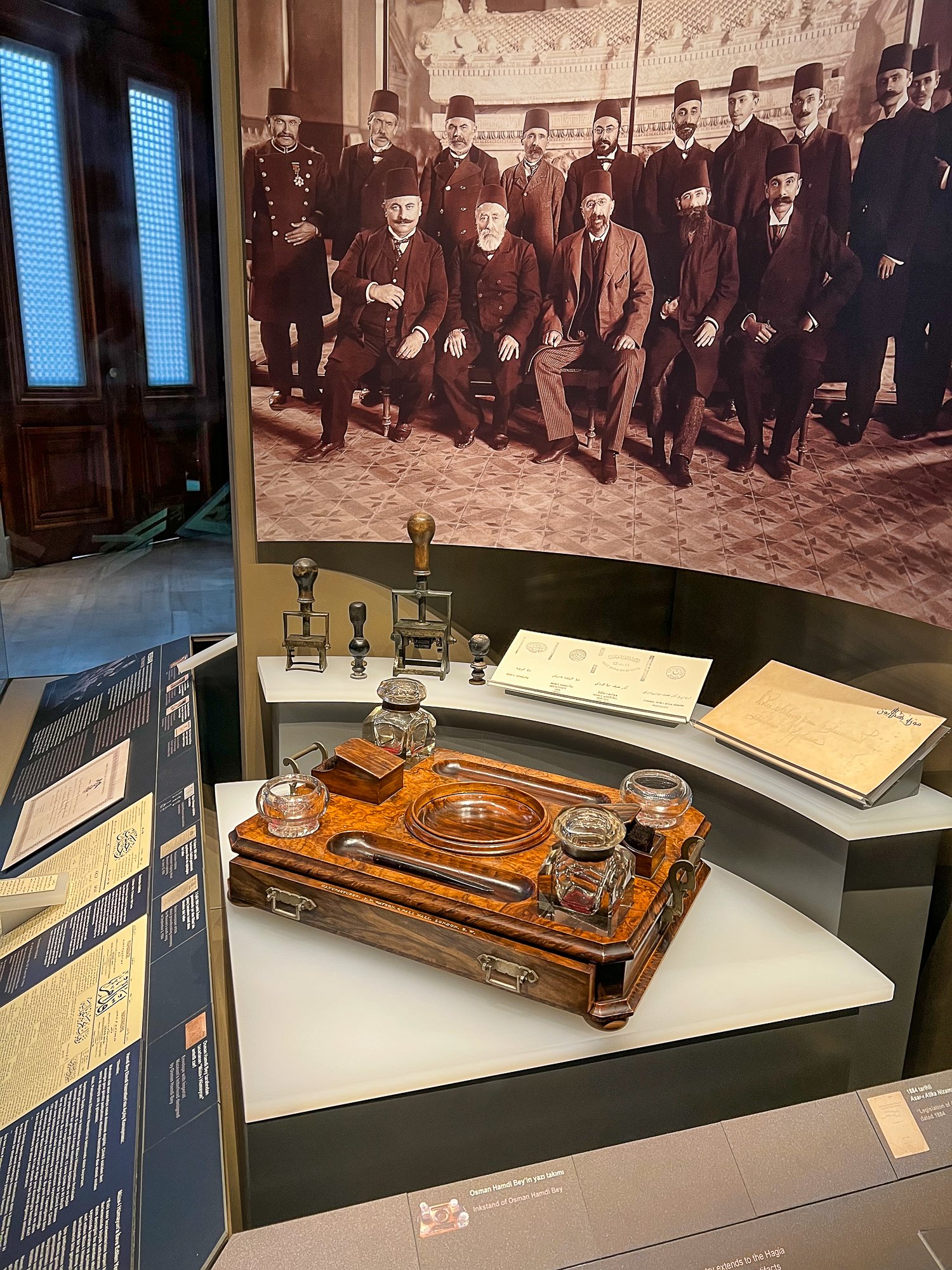

The museum is famous for its displays of funerary art, especially sarcophagi, and justly so. The museum's founder, Osman Hamdi Bey, led an expedition to Sidon (Lebanon), where an ancient Phoenician necropolis was discovered (the Royal Necropolis of Sidon) in 1887, and some exceptionally well-preserved sarcophagi were brought from there. Let’s look at the outstanding examples of sarcophagi from the Istanbul museum.

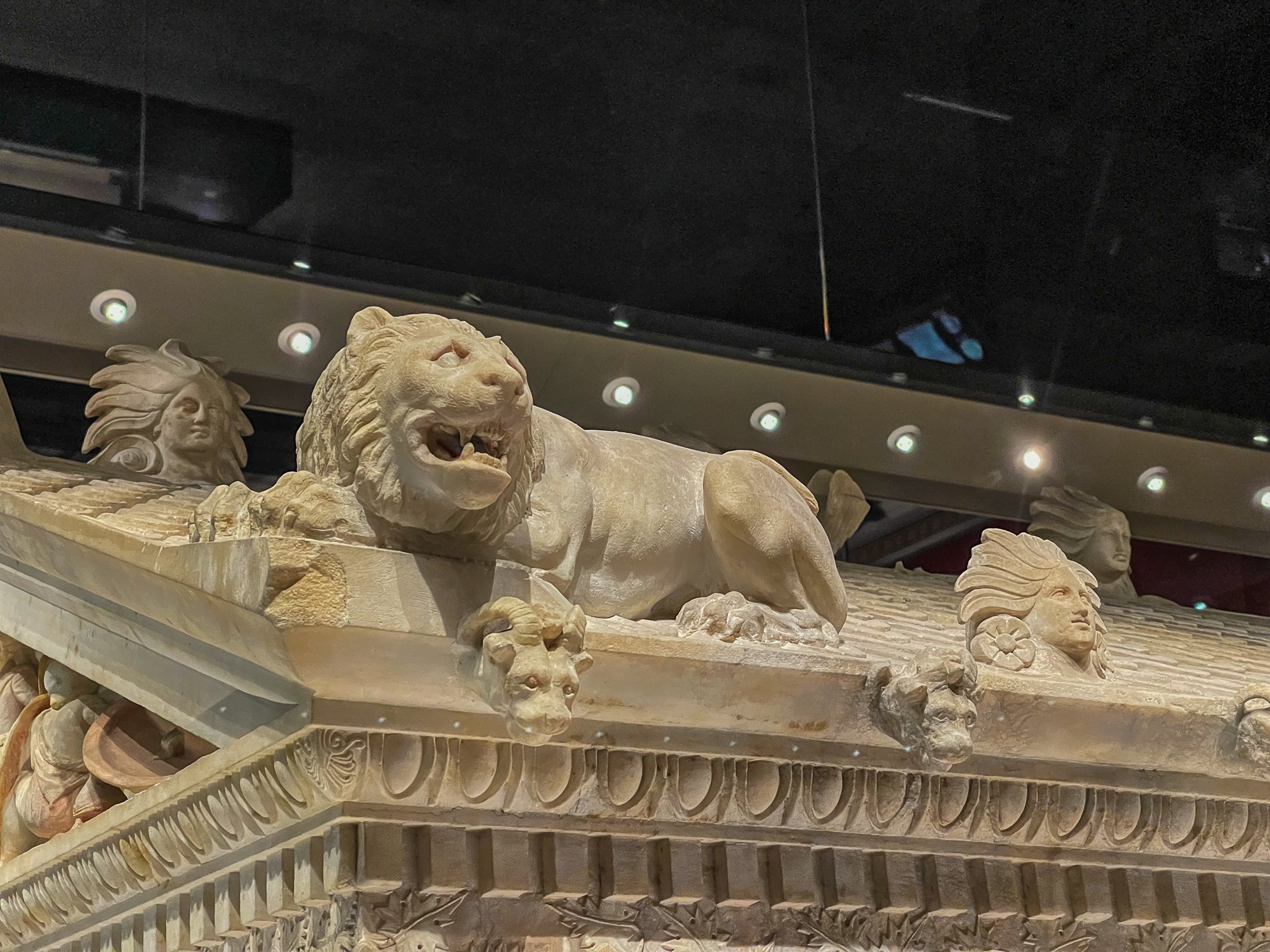

The Alexander the Great sarcophagus is named so because of the bas-relief carvings adorning its sides. They depict the scenes from the lives of Alexander and the future king of Sidon, Abdalomynous. It is a masterpiece between sarcophagi. It is one of the museum's most essential pieces, shaped like a Greek temple, with lions on all corners of the roof and impressive historical and mythological narratives

(Alexander fighting the Persians, Battle of Gaza, Alexander and Abdalomynous hunting lions and panthers) beautifully executed in Hellenistic stone. Note that some soldiers are naked, which was not necessarily uncommon in ancient times. It is also worth noticing an interesting detail; Alexander, depicted in the battle of Issus, wears a lion skin on his head as he prepares to throw a spear at the Persian cavalry.

There are some traces of polychrome detectable, so the sarcophagus most likely was, at some point, covered with colourful paintwork.

Muzeum w Stambule słynie z eksponatów sztuki nagrobnej, zwłaszcza sarkofagów. Założyciel muzeum, Osman Hamdi Bey, poprowadził w 1887 roku wyprawę do Sydonu (współczesny Liban), gdzie odkrył starożytną fenicką nekropolię (Królewską Nekropolię Sydonu) i przywiózł stamtąd wyjątkowo dobrze zachowane sarkofagi. Przyjrzyjmy się wybitnym przykładom sarkofagów z muzeum w Stambule.

Sarkofag Aleksandra Wielkiego został tak nazwany ze względu na płaskorzeźby zdobiące jego boki. Przedstawiają one sceny z życia Aleksandra i przyszłego króla Sydonu, Abdalomynousa. Ten eksponat to arcydzieło wśród sarkofagów. Jest to jeden z najważniejszych elementów muzeum, ma kształt greckiej świątyni, z lwami na wszystkich rogach dachu i imponującymi narracjami historycznymi i mitologicznymi (Aleksander walczący z Persami, bitwa pod Gazą, Aleksander i Abdalomynous polujący na lwy i pantery) pięknie wykonanymi w hellenistycznym kamieniu. Warto zwrócić uwagę, że niektórzy żołnierze na płaskorzeźbach są nadzy, co niekoniecznie było rzadkością w starożytności. Z innych ciekawostek, Aleksander, przedstawiony w bitwie pod Issos, nosi na głowie lwią skórę, przygotowując się do rzucenia włócznią w perską kawalerię. Na sarkofagu widoczne są ślady polichromii, więc najprawdopodobniej był on kiedyś pokryty kolorowymi farbami.

Lycian sarcophagus, dated from 430-420 BC, does not really come from Lycia, but it has the characteristic shape of typical Lycian tombs. It is made from the famous Parian marble (the same Venus de Milo, the Winged Victory of Samothrace, and much of the Parthenon roof tiles were made of). On its longer sides, hunting scenes are depicted (“hunting lion” and “hunting boar”); on the shorter sides, you can spot gryphons (eagle-headed lions). At first, I thought these were dragons, but then I learnt otherwise. Below, the Centaur fights with Lapiths, a scene from mythology often depicted in Art. On the other side, sphynxes are carved with a bird’s wings and a woman's bust and face.

Sarkofag licyjski, datowany na lata 430-420 p.n.e., tak naprawdę nie pochodzi z Licji, ale ma charakterystyczny kształt typowych grobowców licyjskich. Wykonany jest ze słynnego marmuru Parian (tego samego, który był użyty dla Wenus z Milo, Skrzydlatego Zwycięstwa z Samotraki i większości dachówek Partenonu). Na jego dłuższych bokach przedstawiono sceny myśliwskie (polowanie na lwa i dzika); na krótszych bokach przedstawione są gryfy (lwy z głowami orłów). Na początku myśleliśmy, że to smoki, ale okazało się, że nie. Poniżej gryfów Centaur walczy z Lapithami - jest to scena z mitologii często przedstawiana w sztuce. Po drugiej stronie widoczne są sfinksy z ptasimi skrzydłami oraz kobiecym popiersiem i twarzą.

Another piece standing out is the Sarcophagus of the Weeping Women. It depicts eighteen mourning women with shaved heads, bare feet, ragged classical Greek clothes, and saddened faces. The object of their sorrow is most likely the passing of the person laid to rest inside the sarcophagus. We do not know today who this person was, although the size and quality of the sarcophagus indicate it was someone of consequence. One of the theories suggests it was Straton I, a king of Sidon, but not all scholars agree with this hypothesis.

The upper part of the Sarcophagus of the Weeping Women depicts a funeral procession. From the partial traces on the marble, it is suspected that it had been initially dyed blue and red.

Kolejnym wyróżniającym się eksponatem jest Sarkofag Płaczących Kobiet. Przedstawia on osiemnaście kobiet w żałobie z ogolonymi głowami, bosymi stopami, podartymi klasycznymi greckimi ubraniami i zasmuconymi twarzami. Przedmiotem ich smutku jest najprawdopodobniej śmierć osoby złożonej do spoczynku w sarkofagu. Nie wiemy dzisiaj, kim była ta osoba, chociaż wielkość i jakość sarkofagu wskazują, że był to ktoś ważny. Jedna z teorii sugeruje, że był to Straton I, król Sydonu, ale nie wszyscy historycy sztuki zgadzają się z tą hipotezą.

Górna część Sarkofagu Płaczących Kobiet przedstawia procesję pogrzebową. Na podstawie częściowych śladów na marmurze podejrzewa się, że początkowo sarkofag był barwiony na niebiesko i czerwono.

The Sarcophagus of Sidamara found in Konya is the largest and the heaviest (32 tons) known sarcophagus. It dates from the 3rd century and comes from somewhere in Asia. It draws attention with its exquisite engravings depicting some mythological scenes on the side faces, whilst some male and female figures are on the cover. There is an ongoing dispute between scholars whom the figures represent.

Sarkofag Sidamary znaleziony w Konyi jest największym i najcięższym (32 tony) znanym sarkofagiem. Pochodzi on z Azji i jest datowany na III. Uwagę zwracają przepiękne ryciny przedstawiające sceny mitologiczne na bocznych ścianach. Jest tu także kilka postaci męskich i żeńskich. Trwa spór między historykami sztuki, kogo przedstawiają owe postacie.

Mythology is an often-repeated theme in sarcophagi. This one, for example, tells the story of Hippolytus, who rejected the advances of his stepmother Phaedra (the second wife of Theseus). She then accused him of raping her, and he lost his life due to this accusation. This is a Roman sarcophagus from North Africa.

Sceny mitologiczne są często powtarzanym tematem w zdobieniu sarkofagów. Ten na przykład opowiada historię Hipolita, który odrzucił zaloty swojej macochy Fedry (drugiej żony Tezeusza). Urażona Fedra oskarżyła go o gwałt i z powodu tego oskarżenia Hipolit stracił życie. Jest to rzymski sarkofag z Afryki Północnej.

These were just some exquisite examples. This museum section includes a big collection of sarcophagi, funerary steles, inscribed stones, and statuary found throughout the old Ottoman Empire.

Powyżej opisałam tylko kilka przykładów najbardziej znanych eksponatów. Ta sekcja muzeum zawiera dużą kolekcję sarkofagów, steli nagrobnych, kamieni z inskrypcjami i posągów znalezionych w całym starym Imperium Osmańskim.