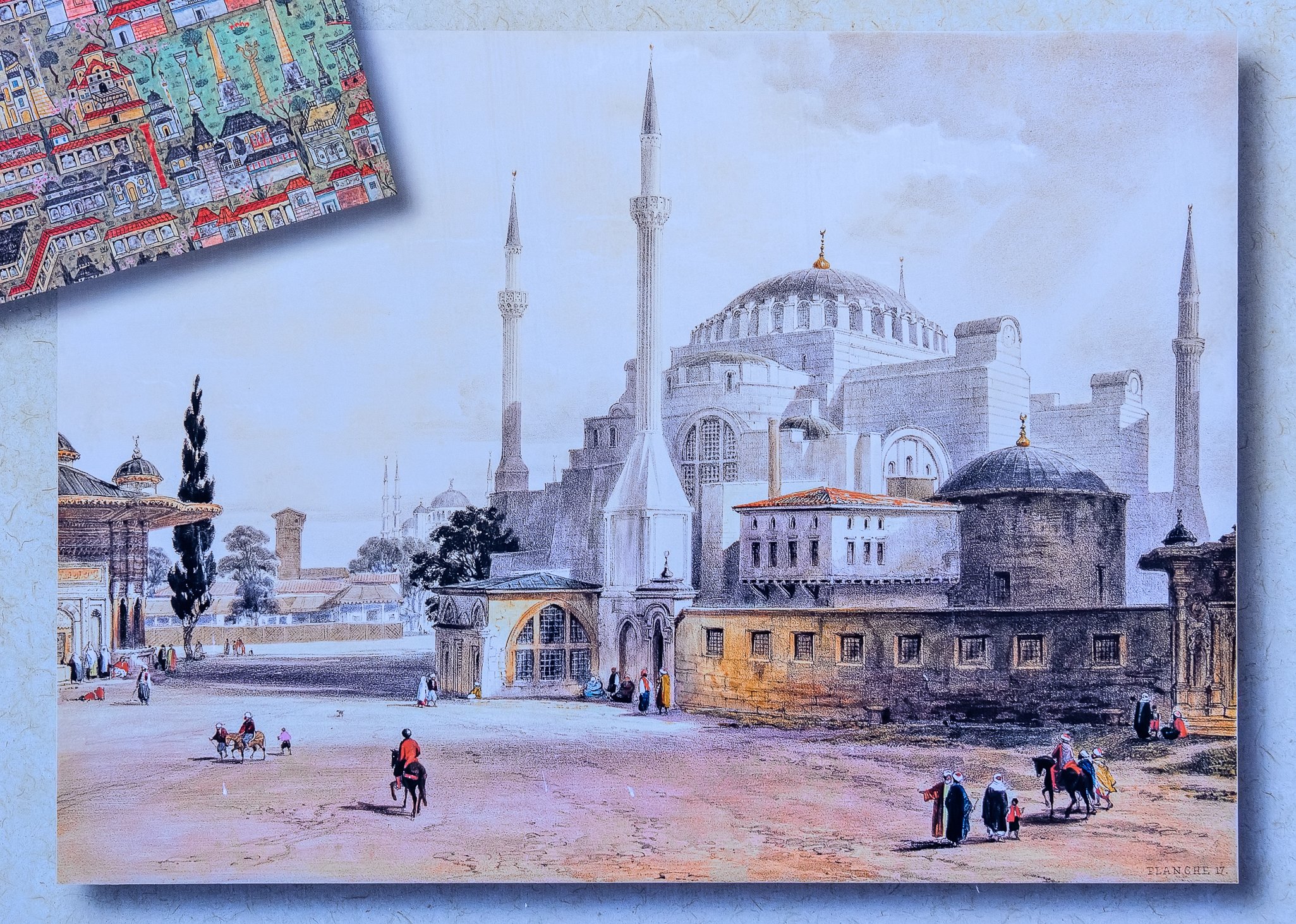

Before we leave Hagia Sophia, we take the side entrance to visit the resting places of XVI and XVII-century sultans. Mehmet III, Selim II, Murat III, İbrahim I, Mustafa I and members of their families are all buried here. Their tombs, if somewhat simple from the outside, have very ornate interiors with elements of calligraphy, Ottoman tile work and paintwork. On the images below Hagia Sophia as seen from the tombs.

Zanim opuścimy Hagię Sophię, kierujemy się bocznym wejściem, by odwiedzić miejsca spoczynku XVI- i XVII-wiecznych sułtanów. Pochowani są tu Mehmet III, Selim II, Murat III, İbrahim I, Mustafa I oraz członkowie ich rodzin. Ich grobowce, choć z zewnątrz raczej proste, mają bardzo ozdobne wnętrza z elementami kaligrafii, osmańskimi kaflami i malowidłami. Na zdjęciach nizej widok na meczet z wejść do grobowców.

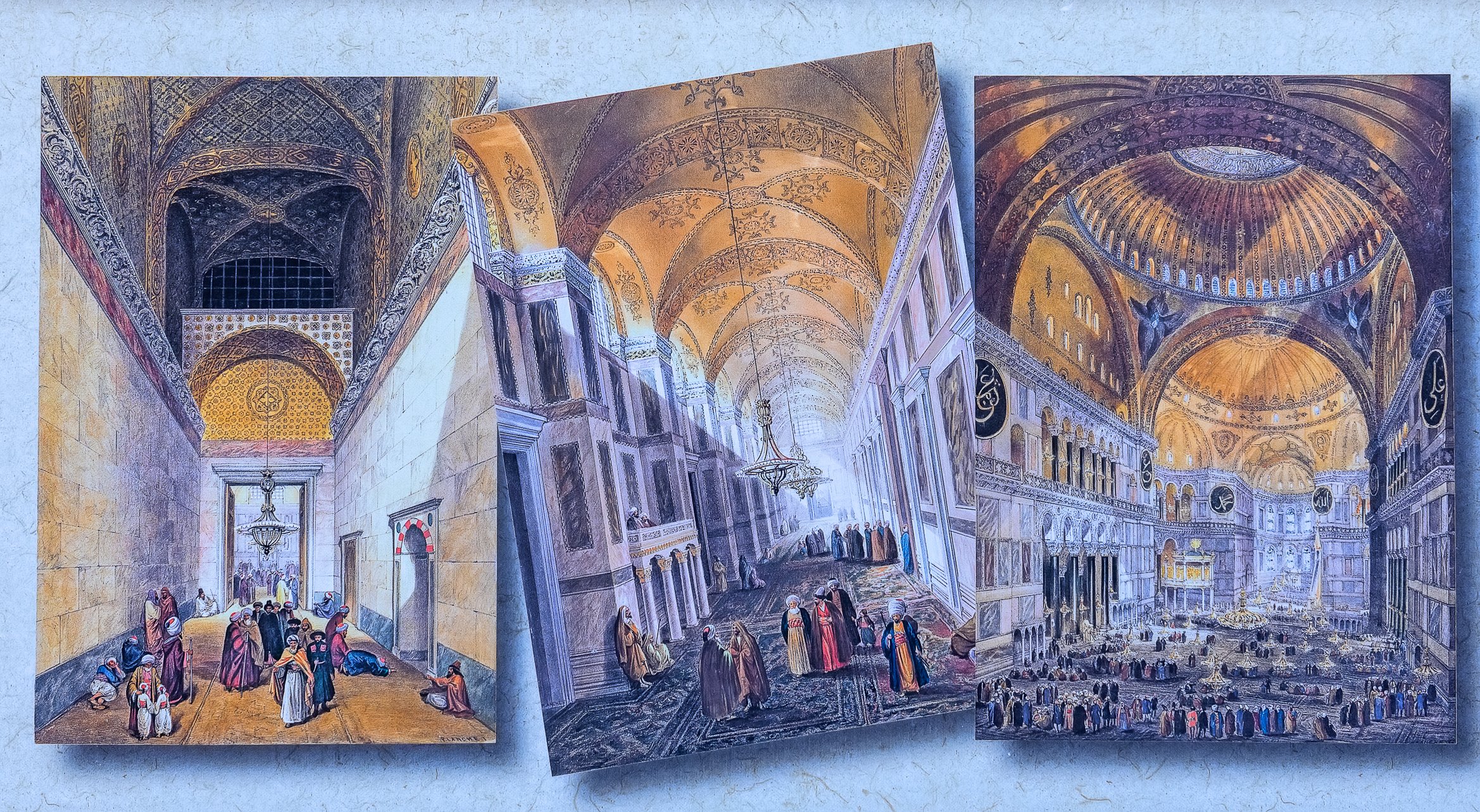

The tomb of Sultan Selim II is one of the most beautiful tombs in Istanbul. The building has an octagonal shape inside but a square outer shell with a three-arched small porch. An external façade is covered entirely with marble. The entrance is decorated with ceramic panels with purple, red, green and blue floral motifs. These tiles are some of the most beautiful examples of 16th-century ceramic art. The right side is original, and the left is an imitation, as the actual one was stolen during renovation and is currently exhibited at the Musée du Louvre. (Marcin is sitting in front of the imitation). The portico has fine examples of stone latticework and marble carving, such as calligraphic panels assembled from polychrome marble.

There are 42 more sarcophagi containing the ashes of the sultan’s wife, many sons and daughters, grandsons, and granddaughters.

Five sons of Selim II were murdered on the same night in December 1574 to ensure the succession of the oldest son, Murat III – a common practice later replaced with the younger siblings of succeeding sultans confined in the kafes (cages) in Topkapı Palace.

19 Murat’s sons were then murdered in January 1595 to ensure Mehmet III’s succession. They were the last ones killed before the cages were invented.

Grobowiec sułtana Selima II jest jednym z najpiękniejszych grobowców w Stambule. Budynek ma ośmiokątny kształt wewnątrz, ale kwadratową strukturę zewnętrzną z trójłukowym małym gankiem. Zewnętrzna elewacja pokryta jest w całości marmurem. Wejście zdobią ceramiczne panele z fioletowymi, czerwonymi, zielonymi i niebieskimi motywami kwiatowymi. Płytki te są jednymi z najpiękniejszych przykładów XVI-wiecznej sztuki ceramicznej. Prawa strona jest oryginalna, a lewa to imitacja, ponieważ prawdziwa plytka została skradziona podczas renowacji i jest obecnie wystawiana w Musée du Louvre. (Marcin na zdjęciu niżej siedzi właśnie przed tą imitacją). Portyk zwraca uwagę wspaniałymi przykładami kamiennej kraty i rzeźby w marmurze, jak na przyklad panele kaligraficzne złożone z polichromowanego marmuru. Wewnątrz, oprócz sarkofagu sułtana znajdują się jeszcze 42 sarkofagi zawierające prochy jego żony, wielu synów i córek, a także wnuków i wnuczek.

Pięciu synów Selima II zostało zamordowanych tej samej nocy w grudniu 1574 r., aby zapewnić sukcesję najstarszemu synowi, Muratowi III – ta powszechna praktyka została później zastąpiona zamykaniem młodszego rodzeństwa kolejnych sułtanów w tzw. kafe (klatkach) w Pałacu Topkapı. 19 synów Murata zostało także zamordowanych w styczniu 1595 r., aby zapewnić sukcesję Mehmetowi III. Byli oni ostatnimi zabitymi przed wynalezieniem klatek.

Sultan Murad III's tomb is one of the largest Ottoman tombs and has a hexagonal layout with two domes, a facade coated with marble, and an arcade in the front. Modest from the outside, it is richly adorned inside, with beautiful examples of coral red İznik ceramics from the 16th century and hand-drawn decorative paintwork. Another characteristic feature is white ceramic tiles on a navy-blue background creating a belt of calligraphic decoration. There are 3 rows of windows. The entrance door of the structure has a Kundekari style, and it is decorated with mother-of-pearl inlays.

Alongside Murad's tomb, there are 54 more sarcophagi belonging to his wife Safiye, his daughters, women of the court and princes.

Grób sułtana Murada III jest jednym z największych grobowców osmańskich i jest zbudowany na sześciokątnym planie z dwiema kopułami, fasadą pokrytą marmurem i arkadami z przodu. Skromny z zewnątrz, jest bogato zdobiony wewnątrz, z pięknymi przykładami ceramiki İznik w kolorze koralowej czerwieni z XVI wieku i ręcznie rysowanymi dekoracyjnymi malunkami. Cechą charakterystyczną są białe płytki ceramiczne na granatowym tle tworzące pas kaligraficznej dekoracji. Są tu 3 rzędy okien. Drzwi wejściowe budowli utrzymane są w stylu Kundekari i ozdobione intarsjami z masy perłowej. Obok grobowca Murada znajdują się jeszcze 54 sarkofagi należące do jego żony Safiye, jego córek, dworzan i książąt.

The tomb of the Princes has a very plain external view, a big dome, brick-covered floor and limestone-covered walls. It seems octagonal from the outside but quadrilateral from the inside. All interior walls are decorated with pen-work plant motifs, hand-drawn ornaments, ribbons and flowers in baskets. In this tomb, 4 princes and the daughter of Sultan Murat III are buried.

Grobowiec Książąt ma bardzo prosty wygląd zewnętrzny, dużą kopułę, podłogę pokrytą cegłą i ściany pokryte wapieniem. Wydaje się ośmiokątny z zewnątrz, ale czworoboczny od wewnątrz. Wszystkie ściany wewnętrzne ozdobione są motywami roślinnymi wykonanymi piórkiem, ręcznie rysowanymi ornamentami, wstążkami i kwiatami w koszyczkach. W tym grobowcu pochowanych jest 4 książąt i córka sułtana Murata III.

The facade of the tomb of Mehmet III is coated with marble. The building has two domes and an octagonal floor plan. There are mural paintings on both sides of the door, which was not the usual style of decorations of that period. Again, three rows of windows are present, and 17th-century white and blue tiles run above the lowest row. Hand-drawn ornaments decorate the remaining parts. New sections for the daughters of the sultans were later added on either side of the entrance gate. The tomb shelters 26 sarcophagi.

Fasada grobowca Mehmeta III pokryta jest marmurem. Budynek ma dwie kopuły i jest zbudowany na ośmiobocznym planie. Po obu stronach drzwi na zewnątrz znajdują się malowidła ścienne, co nie było typowym stylem dekoracji tego okresu. Ponownie występują tu trzy rzędy okien, a nad najniższym rzędem biegną XVII-wieczne biało-niebieskie kafelki. Pozostałe części zdobią ręcznie rysowane ornamenty. Po obu stronach wejścia dodano później nowe sekcje grobowca dla córek sułtanów. W grobowcu znajduje się 26 sarkofagów.

The tomb of Sultan Mustafa I and Sultan Ibrahim I was the former baptistery of the basilica of Hagia Sophia. It is covered with a dome and has an octagonal internal layout. There are also 17 other sarcophagi in the tomb (where daughters of Ahmet I, sons and daughters of Ahmet II and some other members of the dynasty are resting).

Groby sułtana Mustafy I i sułtana Ibrahima I znajdują się w dawnym baptysterium bazyliki Hagia Sophia. Pomieszczenie pokryte jest kopułą i zbudowane na ma ośmiobocznym planie. W grobowcu znajduje się również 17 innych sarkofagów (gdzie spoczywają córki Ahmeta I, synowie i córki Ahmeta II oraz kilku innych członków dynastii).